“It is not the ship so much as the skillful sailing that assures the prosperous voyage.”

George William Curtis

(US American writer, editor and public speaker)

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO INVEST IN STAFF TRAINING NOW?

Falling margins and cost optimization cause financial institutions to save on staff. This affects the number of staff and level of qualification as well as the institution’s willingness to invest in staff training. However, it is important to keep in mind that staff qualification and professionalism play a key role in client acquisition and retention, in building up a financial institution’s reputation and profitability, even at times of fast development of technologies and transition to digital and distance banking.

Today's market conditions dictate the need to optimize the expenditure side of the budget. In the financial sector, staff costs have traditionally formed a significant part of all costs, and optimization usually starts with reduction of staff costs. In present-day conditions, this has been confirmed by managers of business units of large and small financial institutions. Reduction of staff costs, in turn, leads to staff rotation, revision of internal processes, decreasing staff motivation, etc. Under these circumstances, a manager cannot expect employees to adapt to the changing environment without external support. Even under stable market conditions, in order to achieve its goals and implement its development strategy, a financial institution needs to have (1) intelligent staff selection, i.e. a selection process which ensures choosing individuals with appropriate skills, character traits and qualifications for the respective job, and (2) ongoing staff training which is based on the actual training needs of respective staff and the needs of the institution.

In the short term, staff cost reduction can lead to overall cost reduction and cost optimization. At the same time, it is quite possible that expected increase in income will not occur in the medium and long term. The reason may rest precisely in the fact that staff competence, a key to success in any business, is insufficient.

A key point in optimizing training processes and costs is for the financial institution to ensure that staff qualifications and skills are sufficient to meet the institution’s business results.

As an example, we would like to refer to the experience of a large financial institution, which decided to abandon staff training in the short term in order to reduce its costs:

“Already after 6 months of absence of any training at the business unit, the institution observed an obvious decline in employee performance as well as a drastic decrease in the number of clients - old and new. There was also a decrease in the efficiency of business processes and internal communication processes (as a consequence - an increase in the time needed for serving one client, for project approval), as well as a lower level of motivation of key employees, resulting in a further decline of business profitability.”

As this example shows, ill-considered optimization can translate into big losses in the future.

What is the main goal of training?

The goal of training is to provide support to, and improve the efficiency of, staff and with its help – raise the profitability of the financial institution. During times of economic downturn, some financial institutions forget about this and prefer to minimize training costs. It should be pointed out that training should be effective. An appropriate way to reduce training costs is to determine the right, economically sound and effective approach to training. First, it is necessary to understand what exactly you want to teach an employee, and only then select an implementing partner. This means that we should first decide on the target and only then choose the path that will lead us to the intended goal.

Based on the above, we can say the process of choosing the right training topics is of crucial importance. Your choice should be based on actual training needs. Such needs can be of a qualitative nature (what to teach? which skills to develop?), and of a quantitative nature (how many employees and in what departments need to be trained?).

Qualitative training needs can be identified by way of comparing existing staff knowledge and skills against those required for quality job performance. Based on identification of qualitative training needs as shown in Fig. 1 above, you can find out the following:

- the gap between existing and required staff qualification;

- the opinion of all staff of the institution about their individual training needs;

- the ability and desire of each individual staff member to receive training and grow professionally;

- the degree of motivation for development and learning within the institution;

- the training topics that are needed by staff;

- a lot more regarding staff training and development.

The above changes associated with optimizing staff numbers, horizontal and vertical career movements as well as other structural and optimization-related changes will allow you to prepare a comprehensive training plan for a month, a quarter, a year, or even a longer period.

Quantitative training needs can be identified if you know and can correctly assess your financial institution’s economic situation and business environment, its business processes and goals, as well as development plans and then comparing all of this to the quality training needs of each individual employee identified as a result of the analysis (evaluation results, scores, testing results, questionnaires, other).

This will form a basis for an effective solution regarding the target groups of training: how much and what training is needed. This will allow you to optimize the training process and its budget, while ensuring the necessary quality of staff. This is assuming that new staff members have been selected that meet corresponding job requirements and have the personal characteristics, qualities and qualifications needed.

When planning and organizing training, it is important to categorize employees and then determine the appropriate approach to each category based on their level of competence as well as the organizational structure of the financial institution and the specifics of its business processes.

Sometimes you can hear statements such as "Experienced employees do not need any training, they already know everything!" However, it should be pointed out that it is exactly employees of this type that often are the fastest learners. In addition, training can provide additional motivation for these employees who can become multipliers, train other (newly recruited or less experienced) staff and push business forward.

Under present conditions, where the struggle for each client is becoming visible, each leader must find the right way to improve the qualification level of staff since the price of errors of incompetent employees can be too high for business.

Training topics are designed to provide an employee (a group of employees) with the skills and knowledge that can be applied in practice immediately after training and developed in the long term. For example, if an institution notices that the number of eligible clients is decreasing, that it is getting increasingly difficult to acquire new eligible clients, then the topic “Client acquisition/Sales” should become a top priority. If a period is marked by an increase in the number of problem loans, then the topic “Dealing with problem loans” deserves primary attention. Whenever preparing a training curriculum or an individual training event, an institution should bear business objectives and goals in mind.

Another aspect to be considered in the process of training and training cost optimization is “Who will be the trainer?” Training can be both internal (on the basis of an in-house corporate training structure) or external.

Obviously, it makes sense to use internal training capacities, if they exist and have the quality and capacity needed for the purposes of training staff in a timely manner and at the quality level aimed for. If not, then financial institutions should look into acquiring such training from an external provider. External providers should be carefully screened and their offers compared with a view of finding the best ‘fit’ in terms of topic, level, price, frequency, etc.

It should also be noted that training providers often offer ‘open training’ as well as ‘closed training’. Whereas closed training would only be open to a selection of participants, open training would be accessible to participants from a variety of different institutions. Frequently, closed trainings would also be organized for a specific financial institution. This has the big advantage that the trainer would adjust respective training to the specifics of the financial institution. The big advantage of attending open training is the variety of its attendants, which allows to compare different approaches, etc.

If you delegate specialists to open trainings, it is important to understand:

- Which company conducts the training?

- Does the topic of the training meet the business needs of your institution and staff?

- Who are the trainers?

- What is the target audience for the training?

- What employees need this training?

Speaking generally and specifically, when it comes to training, financial institutions tend to be ‘penny wise and pound foolish’, which in turn - as was demonstrated above – may have serious adverse effects on business. More specifically, instead of hiring an experienced external trainer, financial institutions tend to instruct their staff to acquire new know-how themselves or they may prefer to hire less costly trainers without any critical selection based on the trainer’s actual qualification and in-depth knowledge of the subject. Thus, from the very beginning, some financial institutions lay the foundation for spreading know-how and knowledge of lower quality, which again leaves these institutions with undertrained or poorly trained employees.

Therefore, we would like to emphasize the importance of carefully selecting training providers and of choosing providers who will add value by improving staff skills, staff know-how and expertise, and, ideally, support institutions in growing their own knowledgeable multipliers who would become professional in-house trainers after successfully completing appropriate training.

Especially large institutions may maintain very strong own training centers, which can cover nearly all topics that may be needed. However, especially for smaller institutions, it usually makes sense to combine internal and external training. In this way, the scope of topics that can be meaningfully addressed increases significantly.

And finally - a quote from the sequel of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

ANALYSIS OF FINANCIAL RATIOS FOR THE PURPOSES OF MONITORING PROBLEM LOANS

This paper focuses on the analysis of financial ratios which can be used in case of problem borrowers and/or borrowers whose business shows adverse trends potentially jeopardising successful loan repayment. These financial ratios may be helpful in assessing risks and prompt decision-making regarding further steps to be taken concerning borrowers.

Additional financial ratios and indicators are especially useful when a financial institution’s portfolio at risk is growing and economic losses of clients become noticeable.

Financial ratios are an important tool in analysing business clients (for more information on financial ratios please see an e-lesson on the RSBP Knowledge sharing and exchange platform www.rsbp-ca.org).

Apart from the basic ratios used for the analysis, in case of problem loans, we can recommend the following additional indicators:

- Break-even point

- Liquidity

- Inventory safety margin (financial stability ratio given inventory)

- Total equity-to-debt ratio (ratio of equity to total credit exposure).

Break-even point (BEP) in money terms

The BEP shows the minimum sales volume in money terms that allows a company to break even, i.e. to operate without profit or loss (at a zero profit). There are several formulae used for BEP calculation. The most common formula used in analysis of micro and small enterprises (MSEs) is the following:

FC – total fixed or quasi-fixed costs (actual costs of the reporting period)

FE – family expenses

I – total interest accrued (on all business loans)

S –sales revenue

VC –variable costs

The BEP is used for the analysis of sales trends and shows the volume of sales a client should maintain in order to match his/her liabilities (excluding loan principal instalments) without affecting owners’ equity. The BEP is useful when considering debt restructuring.

Since business and family cash flows are difficult to separate and a business is often the main or even the only source of funding for a family budget, it is recommended to include family expenses in the BEP calculation for the MSE segment.

Please be careful in your calculations as the BEP is not stable and may change depending on the conditions of business operations. For example, costs will usually inevitably increase as a result of production expansion or the opening of new points of sale: additional premises will lead to higher rent expenses, and hiring additional staff results in a rise in payroll costs, etc. Business growth will result in a higher break-even point.

If business conditions remain unchanged but the break-even point increases, this can be a signal of a company’s deteriorating financial condition.

The importance of the BEP in analyzing a business can also be seen when the BEP is compared to other financial indicators. For example, when analysing sales trends, the BEP can be used to calculate profitability for respective periods.

Liquidity

Deteriorating business conditions primarily affect liquidity levels of a company. In order to maintain their sales volumes, companies may increase the share of sales at deferred payment conditions, thus increasing the share of accounts receivable. The result: there is a profit, but there is no cash to repay debts.

Available liquidity as of the date of the balance sheet allows to draw conclusions about a company’s ability to make timely loan payments. Available liquidity can be determined by drawing up a Cash Flow statement. There is also another method of determining liquidity without preparing a Cash Flow statement:

L – liquidity

OCB – opening cash balance

TCF – total cash inflow for the period

OCF – other cash inflows

P – purchases made and paid within the analysed period

TFC – total fixed costs

TI – total instalment on all loans, incl. consumer loans

FE – family expenses

This indicator shows the immediate liquidity of a business. It can also be used for liquidity projections for the upcoming months, which is especially useful for businesses with pronounced seasonality.

Inventory safety margin

It is not uncommon for a business to maintain acceptable liquidity levels and meet existing liabilities although actual financial results may be negative. In order to meet its liabilities, a business could use proceeds from the sale of fixed or working assets (more commonly, inventory). As a result of declining investments in inventory, the inventory volume decreases, thus affecting not only the financial result but also the very existence of the business in itself. An ill-considered inventory reduction can lead to a shut-down of the business and, thus, jeopardize loan repayment.

For the economic assessment of such business situations, we recommend calculating the inventory safety margin. This ratio shows the number of months that a client can cover liquidity needs using existing inventory, provided all other business conditions remain unchanged.

ISM – inventory safety margin

NP – net profit of the period (month)

TI – total instalment for all business loans

This indicator should be compared to the number of months remaining to loan maturity. If the number of months remaining to loan maturity is more than the ISM, this signals the need to take a management decision regarding loan roll-over, early loan repayment with proceeds from the sale of company assets, etc.

However, it should be borne in mind that in most cases a decline in inventory will lead to a decline in sales volume and, accordingly, to a lower financial result as well as a lower inventory safety margin.

Equity-to-debt ratio (total equity to the aggregate outstanding principal)

Businesses tend to use several sources of finance and, especially if business is going down, businesses will try to use all available sources of credit with a view of delaying payments or building up inventory in the hope of generating more sales, etc. Nowadays, it is also not uncommon for borrowers to have several outstanding loan products, and the small business segment is no exception.

The equity-to-debt ratio helps loan officers to assess the degree of client-reliance on external financing and shows the ratio of the owners’ total equity (in the business and beyond the business) to the aggregate outstanding loan principal, including consumer loans.

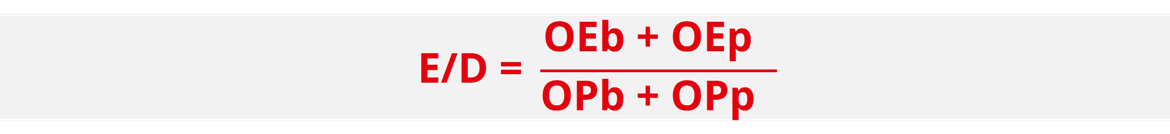

E/D – owners’ equity to debts

OEb – owner’s equity in the business,

OEp – owner’s equity beyond the business (private),

OPb – outstanding principal of all business loans,

OPp – outstanding principal of all private loans

For micro businesses and the lower-end segment of small businesses the recommended minimum for this ratio is 1. It is important to remember that - especially for micro and very small businesses - the amount of debts should not exceed the owner’s/owners’ own stake in the business. If the amount of all current loans is larger than the borrower’s total equity, the risk for a financial institution is very high.

Needed data

For the calculation of the above ratios, at least the following data needs to be obtained from the borrower:

- the amount of sales in the last month (immediate and with deferred payment);

- changes in pricing policy (trade mark-up, profitability of production)

- the amount of cash inflow in the last month;

- the amount of purchases in the last month (immediate and with deferred payment);

- fixed or quasi-fixed costs (payroll, taxes, rent, transport costs, etc.);

- family expenses (including changes in income of other family members);

- the sum of all current instalments (on business and consumer loans) from all financial institutions, subject to possible changes[1];

- liquidity;

- available inventories;

- fixed assets;

- accounts receivable and payable with respective repayment deadlines;

- outstanding loans from other financial institutions[2]

[1] Even better is to include all other obligations, if available, including from informal sources, but it is not always possible to get this information; furthermore, repayments may be more negotiable than in formal finance

[2] See above

Case study:

The client is a retail trader in silver jewellery. In June, the client received a working capital loan in the amount of 500,000 for 16 months (with a monthly loan instalment of 35,000). In recent months, the client has violated the loan repayment schedule. In the course of monitoring (in January of the year following the reporting year), the loan officer gathered the following information:

|

The client is a retail trader in silver jewellery. In June, the client received a working capital loan in the amount of 500,000 for 16 months (with a monthly loan instalment of 35,000). In recent months, the client has violated the loan repayment schedule. In the course of monitoring (in January of the year following the reporting year), the loan officer gathered the following information: |

|

|

Sales of the past few months |

October – 400,000 November – 250,000 December – 325,000 |

|

Variable costs |

October – 307,692 November – 192,308 December – 250,000 |

|

Fixed and quasi-fixed costs, including all interest accrued |

40,000 |

|

Family expenses (including repayment of a consumer loan) |

20,000 |

|

Cash in hand |

0, since all accumulated cash was used to repay loan instalments. |

|

Opening cash balance at the beginning of the previous period |

0, since all accumulated cash was used to repay a loan instalment (in December) |

|

Inventories |

400,000 |

|

Inventories as of the date of the loan disbursement |

500,000 |

|

Outstanding principal balance of a business loan |

280,000 |

|

Outstanding principal balance of a consumer loan used for the purchase of real estate |

1,000,000 |

|

Owner’s equity in the business |

500,000 |

|

Owner's equity beyond the business |

1,500,000 |

|

Cost of merchandise inventories purchased last month |

230,000 |

For the calculation of the BEP, we use the average amount of sales for the past three months – 325,000 ((400,000+250,000+325,000)/3) and the average variable costs – 250,000 ((307,692+192,308+250,000)/3).

The resulting BEP will look as follows:

So, for the company to breakeven, its minimum sales volume should be 260,000. If we compare this to the client’s actual sales, we see that the November result was negative.

Failure to comply with the repayment schedule indicates liquidity problems at the client’s business.

The estimated liquidity as calculated will be:

Calculated liquidity confirms that the client provided correct data.

The average monthly net profit of the last three months is 15,000 (NP=325,000–250,000-40,000-20,000). This profit amount cannot cover the current loan instalment. The client must have been repaying the loan at the expense of inventory, which is gradually decreasing. This assumption is confirmed by the decreasing inventory balances.

Inventory safety margin:

The entrepreneur will be able to maintain the liquidity of the business at the expense of the current volume of inventory for 20 months, provided that the business situation does not change. Given that there are only 10 months remaining to loan maturity, the entrepreneur should be able to manage this credit exposure and the business should be able to continue.

The equity-to-debt ratio calculation:

Total business and private equity is 1.56 times higher than total liabilities. This ratio is within the acceptable norm (i.e. >1).

Conclusion:

The client has been in breach of the repayment schedule due to the overall deterioration of the financial and economic condition of the business, which is confirmed by monitoring. The calculated ratio values helped to determine the degree of this deterioration, but showed that the client should be able to manage the current loan burden and keep her business running. However, the client has certain liquidity problems, so we can recommend reviewing the client’s payment schedule, more specifically, splitting the loan instalment into two (or three) smaller instalments. This will help the client to shorten the period of liquidity accumulation.

Another possible option is to find a more suitable date for instalment repayment in consultation with the client and by moving the date to a date where there are no other payments. In addition, regular monitoring should be done to prevent a possible default in case of deteriorating business performance.

The financial ratios described here, along with other financial tools used in analysing business, allow for identification of problems and difficulties at client businesses and, therefore, for prompt reaction to any changes in the business situation and for taking appropriate action to avoid default and resolve problematic debts.

Acronyms and abbreviations

|

Term |

Explanation |

|

AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

|

AISP |

Account Information Service Provider |

|

AML/CFT |

Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) |

|

API |

Application Programming Interface |

|

B2C, B2B, C2C |

Business to Consumer, Business to Business, Consumer to Consumer |

|

CBS |

Core Banking System |

|

DFA |

Digital Field Application |

|

DFS |

Digital Financial Services |

|

FI |

Financial Institution |

|

MIS |

Management Information System (CBS and other integrated systems) |

|

mPOS |

Mobile POS (Point of Sales) |

|

MNO |

Mobile Network Operator |

|

MSME |

Micro, Small and Medium Entrepreneur |

|

PSD2 |

Payment Service Directive Revised |

|

PSP |

Payment Service Provider |

|

P2P |

Peer to peer |

|

QR code |

Quick Response code, a two-dimensional barcode |

|

VAS |

Value-Added Services |

Executive summary

In this paper the author presents the journey towards digital transformation that financial institutions (FIs) are gradually embarking onto. The aim of this paper is to help demystify this growingly complex technological question, rife with buzzwords and new concepts. The main focus is on what the author deems meaningful and practical for FIs in transition economies, respectively in Central Asia.

The author describes some general trends observed in more mature markets, which are likely to become relevant to developing countries and countries in transition, introduces terminology that is emerging as industry-standard, explains the distinction between digitization and digitalization, and describes the basics of digital transformation. The author provides some examples in order to illustrate main principles, but these examples are by no means meant to express any view or judgement about these cases. Finally, the role of regulators is discussed and an example presented of how Payment Service Directive Revised (PSD2) is affecting European banks.

One key message the author would like to convey is that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’: local conditions, positioning of FIs, competition, structures of the respective market and – naturally – strategic objectives of the FIs themselves can lead to various rational approaches. At the same time, the author would like to insist that inaction is not an option and we will provide some high-level actionable advice for FI executives.

Digitization, digitalization and digital transformation

Terminology

In this part, we will provide a definition of key concepts, which are often confused or misunderstood, but useful for accompanying you along your digital transformation.

Figure 1: The digital transformation ladder

Digitization

Strictly speaking, digitization means converting information stored in analog formats (i.e., paper, voice, pictures, etc.) into a digital format, so that computers can store, understand and treat this data. Most FIs have been actively digitizing their activities for decades: implementing systems such as core banking system (CBS) or management information system (MIS) to store and automate processing of business information. Some institutions, especially those engaged in microfinance activities, have been working with Digital Field Applications (DFA) for ten years or so. They equip their field staff (loan officers or customer relationship officers) with tablets or smartphones, enabling collection of information in digital form while visiting customers and potential customers at their premises. This permits to progressively phase out paper-based forms, ensure better quality of data and faster business operations (e.g. credit underwriting/decision making).

Major outcomes are the lowering of loan turn-around-time and overall improvement of portfolio quality due to a more systematic and optimized collection, processing and analysis of customer business data. Once collected, customer data is treated by the system and presents insights for the credit committee/loan decision maker. If a credit-scoring model is also digitized, loans can be fully automatically assessed and disbursed. Digitization is also achieved through the spread of mobile and internet banking, which reduces the brick-and-mortar presence of FIs and, at the same time, allows FIs to deepen the digital footprint of customers.

The concept of big data1 has been widely discussed in recent years. While some aspects are relevant and promising, far too often FIs are tempted to leapfrog and plunge (and invest) into it without having first established sound data management and a sound data strategy. We would notably advise to first:

- Ensure solid data management, put into place through a dedicated business person or group in charge of defining and implementing data policy and strategy within the institution;

- Prepare and maintain a data inventory: which data does the FI have available? Where is it located (in which system(s))? And, more importantly, which data is required and not yet available (or at least not yet digitized)? And, lastly, lay out a strategy to acquire needed data;

- Control data quality: overcome problems due to data redundancy and its corollary: inconsistency;

- Make sure data is cleaned up, compiled in a meaningful manner and can be accessible to business executives in a practical way (via tools such as business intelligence, analytical reporting systems, etc.).

Digitization is a first necessary and important step along the journey. It is also a never-ending story: when new products or services are developed, all too often, decision-makers fail to think “digital” and create new paper-based forms. It requires a lean approach to ensure the constant reduction of “hard” information.

Digitalization

Digitalization refers to providing financial services via digital channels. This can be achieved by FIs on their own or as partnerships between FIs and other firms. The following examples draw on Digital Financial Services (DFS) associated with e-commerce providers and payment services providers (PSP). Among other widespread cases, one can also list partnerships involving a mobile wallet provided by Mobile Network Operators (MNOs).

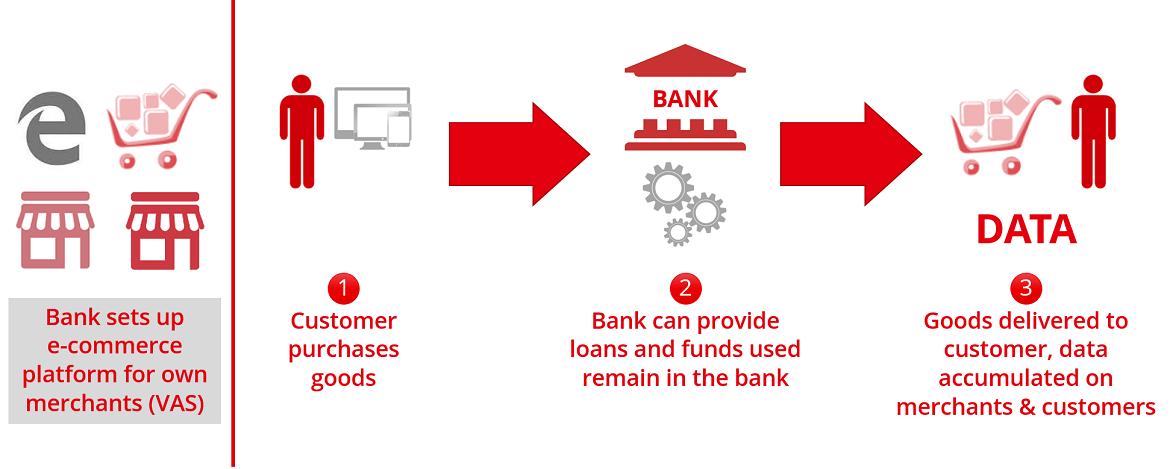

Case 1: FI-led e-commerce platform

Figure 2: e-commerce platform created by a FI

This case is about a bank dominating retail operations in a fairly mature market. In order to promote interaction between its individual customers and its micro-, small- and medium sized enterprise (MSME) customers, the bank offers its MSME customers the possibility of setting up an e-shop (a value-added service for MSME customers) and accepting digital payments (e.g. by cards) when selling their goods and services to, for example, individual customers. Individual customers can also shop at these MSMEs using a consumer loan streamlined to the online sales process and thus expanding the volume of the bank’s activity.

There are also secondary advantages to this type of scheme:

- The funds remain within the institution (when a sale is performed, the money goes from the individual customer account to that of the MSME customer – both held at the bank);

- The FI gathers more information about its customers (for individuals, it collects consumption-related patterns. At the same time, the same information can also be used to understand sales turnovers of MSME customers better).

Business to consumer (B2C) is not the only model for e-commerce: other cases could involve a business to business (B2B) market place for suppliers of micro business customers (e.g. a platform where wholesale suppliers of inputs sell to small farmer customers of the bank) or even a consumer to consumer (C2C) model fostering intra-individual customer transactions, such as small-scale sales similar to those through classified ads. We can think of P2P platforms where some sales and purchases of goods between individuals could be organized by an FI that would supply financial services to facilitate such transactions (e.g. credit or digital payment services).

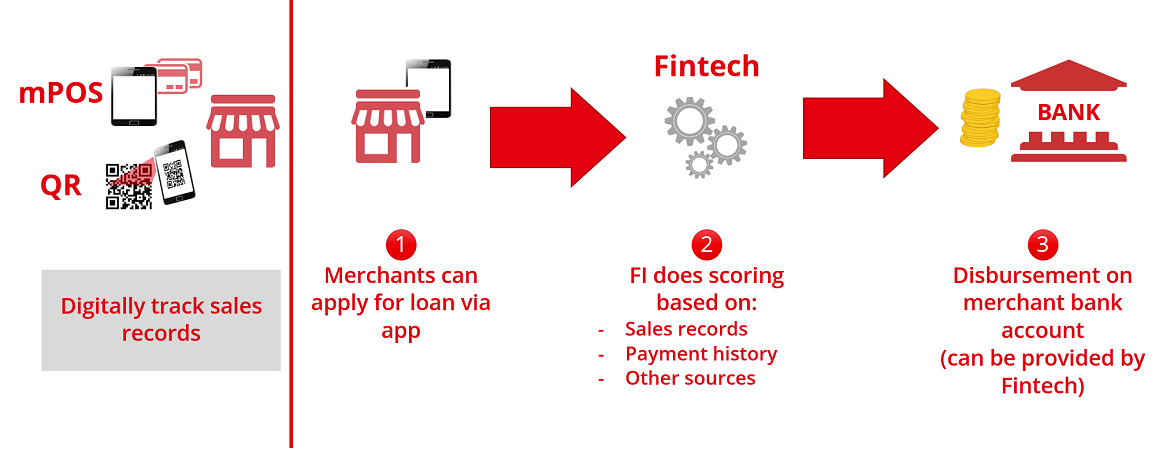

Case 2: Digital payment platform

Figure 3: Financial ecosystem around a payment service provider (PSP)

In markets of various maturity some Fintech payment service providers (PSP) are providing digital payment services to MSMEs, either by cards (notably using mPos) or by other means such as quick response codes (QR codes) or social network-based transfers. In the past, many MSMEs usually only accepted cash payments and were often unable to provide a reliable track record of their sales history, necessary to establish the credit-worthiness of their activity. Thanks to these digitized transactions offered by PSPs, MSMEs are now able to substantiate their business activity levels and have become eligible for loans provided by PSPs or partnering FIs.

Some fintechs have been able to obtain other information about MSMEs from other sources as well, such as sales history from global online B2C market place platforms or shipping service companies. Fintechs can also provide MSMEs access to other value-added services, such as online simple stock and accounting management solutions, based on the use of which these fintechs can further analyze MSME business performance. In case these MSMEs do not have bank accounts, the banks collaborating with the respective fintech can acquire these clients for account opening and even issuance of debit or credit cards.

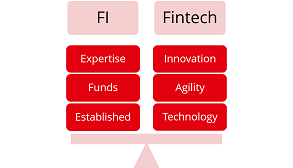

Digital Financial Services (DFS) provided by FIs and fintechs

Digital financial services (DFS) can be provided by either fintechs or traditional FIs. There is always room for collaboration and the lines between fintechs and FIs tend to blur. For example, while this is still exceptional, some major fintech firms in the USA are now applying for banking licenses. Fintechs progressively cover the spectrum of financial services provided by traditional actors. At the same time, we see some FIs gradually investing in e-commerce platforms or working more closely with fintechs to supply these fintechs with services only FIs can provide. A recent survey by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) identified that roughly 80% of large FIs are seriously considering investing in fintechs and that they expect a return on investment of close to 20% over these efforts.2

Another important takeaway is to understand that data itself is sought after. Data is no longer just a means to an end but an end per se, and end in itself.

Digital transformation

Digital transformation is a longer-term evolution of the nature and business – in our case - of FIs. This phenomenon will radically change how banks operate, what their business lines look like and how the will interact with the whole financial ecosystem. Within the next 5 to 10 years, most FIs will have to transform, to open their systems and learn how to cooperate with other sorts of (hybrid) firms, fintechs and others. One obvious and already existing novelty is ‘open banking3’: FIs provide their existing infrastructure and systems “as a service” to different types of non-regulated companies (e-commerce portals, PSPs, insurance companies, cryptocurrency exchanges, remittance service providers, etc.). Most of this type of cooperation will be with fintechs.

Let us now look at how fintechs and FIs can cooperate or compete.

Fintechs: friend or foe?

What are fintechs?

Fintechs are financial technologies companies using high and new technology which are providing financial services and competing or cooperating with FIs. Overall, they are more agile than traditional FIs and invest more in technology aimed at addressing one particular question, for example providing loans to farmers using artificial intelligence (AI) or alternative sources of data.

Fintechs are more agile in the sense that they typically are smaller firms, capable of rolling out new products or changes faster and with less effort than a – typically – larger FI. The fact that fintechs typically are trying to solve one specific question also makes them more prompt to adaptation. In terms of use of high technology, surveys have found that some 46% of large fintechs have invested in AI while only roughly 30% of large banks have.4

|

Fintechs |

Traditional FIs |

|

Agile |

Bureaucratic |

|

Horizontal culture |

Vertical culture |

|

High-tech (e.g. AI) |

Low-tech (legacy CBS…) |

|

Highly specialized |

Broader spectrum of clients |

|

Light regulation |

Heavy regulation |

Figure 4: Comparative advantages of Fintechs over traditional FIs

Are FIs now irrelevant?

“Banking is necessary, banks are not” (Bill Gates, 1994). For some time, it was a widespread view that classic FIs, foremost banks, would become obsolete. However, banks are still here 25 years later. In recent years, it has become clear that fintechs have limitations as well and that banks still can bring a lot to the table. Notably, banks/traditional FIs have the following strengths that are valuable in partnerships:

- Large existing customer base and associated data;

- Cheaper access to capital;

- Existing risk management procedures and systems dealing with AML/CFT;

- Infrastructure (branches, information systems, ecosystem connected to PSPs, etc.);

- Expertise about markets in which they operate;

- Licenses, i.e. they are regulated which gives some comfort/lowers some risks;

- Credibility and visibility (brand name).

Fintechs cannot easily compete on the points above and do not necessarily want to do so. The last thing most fintechs would want, especially newcomers, is to set up a heavy CBS or obtain a banking license: they would rather collaborate with FIs endowed with such assets and benefit from the existing infrastructure etc. to sell their services.

Figure 5: Best of both worlds

In the next part, we will share some insights about the European experience and demonstrate how the regulator in the EU pushed for deepened cooperation between FIs and fintechs.

Regulatory aspect: the European example

Regulatory aspect

A regulator can decide to protect an existing industry, making it harder for newcomers to enter the market. Alternatively, in other cases, a regulator can force some of the existing players to share information with newcomers in order to make it easier for newcomers to become established and to promote competition among players. In recent years, we can observe this trend in Europe, as the regulator is pushing for further integration of the EU market.

What is PSD2?

The Payment Service Directive Revised or ‘PSD2’, issued in 2016 and coming into force in 2018, is a new regulation affecting some 9 000 banks in 29 European markets. It is aimed at further unifying the banking sector of the European Union and at enhancing competition among banks (and other institutions engaged in this field) in Europe.

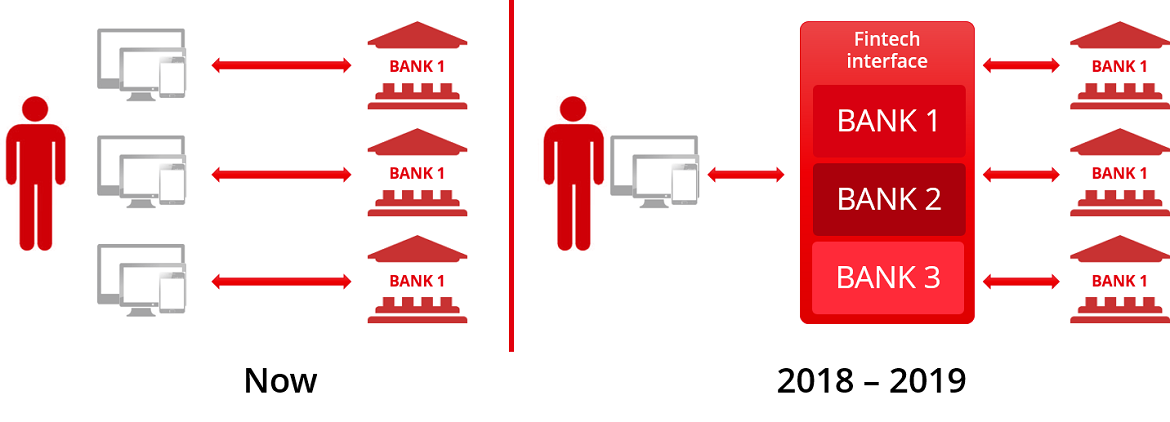

Without delving into details, one of the main consequences of PSD2 is the appearance of Account Information Service Providers (AISP). Existing FIs and new players (typically fintechs) will have the possibility to register as AISP and then - with the consent of the account holder - to fetch lists and details of operations performed on a given account in an automated manner. This will allow individual account owners holding accounts at several banks and possibly in several countries, to share their information with an account aggregator. One of the major implications is that individuals may then not only use their own accounts, their own banks’ internet or mobile banking services for transactions, but those of third parties as well. This will increase competition between banks, banks and fintechs, and is expected to be reflected in improvements in quality of service and lower costs for users of financial services in Europe.

Figure 6: Impact of PSD2 in terms of account information aggregation for online and mobile banking

An example of services that could be built upon this evolution could be an artificial intelligence-powered bot providing financial advice to customers on where best to invest their funds based on the combined information about the customer across several banks. This naturally could also be applicable to credit as well. Financial services may not only be delivered by traditional FIs (including those holding accounts of the customer) but also by third-party financial service providers such as dedicated Fintechs.

Risks and opportunities

In the case of Europe, it is expected that traditional banks will have a hard time retaining their current customers. Especially millennials are more likely to migrate their accounts to new players (e.g. especially to institutions with accessible and user-friendly online and mobile banking platforms).

PSD2 is a critical game changer and traditional FIs are now seeking partnerships in order to stand out from the crowd and remain in the race. The most advanced FIs have already started opening their systems and offering “bank-as-a-service” type of new business products so that fintechs can “piggyback” onto existing systems of FIs and offer their services to the established clientele of such FIs. Open banking and platformification5 of banks are unlikely to be just a trend: they reflect a long-term evolution of the industry.

Those institutions dragging their feet will suffer while those embracing these changes have opportunities for reaping the benefits of their efforts across the European market. Naturally, this will entail significant investment in information systems so that FIs can open their systems to third-party players. We can also expect an increase in cyber-criminality and information theft.

While Europe is a specific case, it would be surprising if similar regulation would not also appear in other parts of the world in coming years.

Conclusion

FIs will face numerous challenges on their digital journey and technology-related issues are not necessarily the thorniest. IT system and data management are going to play a strategic part at organizations. The entire approach to business may be expected to be impacted and FIs need to rethink their business in principle. Foremost this concerns how to acquire, engage and retain customers. Brick-and-mortar branches are going to be phased out and relationships with customers will be conducted increasingly via digital channels. Risk and audit departments will also be affected by automation and the deployment of DFS. Against this background, human resources management is gaining in importance and HR departments are becoming of key importance in terms of ensuring that institutions are staffed with competent labor at the right time as well as in terms of supporting – where possible - transition of existing employees to the digital world.

While there is sequential graduation from digitization to digitalization and digital transformation, all these steps remain relevant and it is easy for FIs to slip back into old habits and reinstate some paper forms as existing MIS may not always be able to evolve as quickly as the creativity of bankers. New channels are likely to be used to provide existing products - some in partnerships, others using channels fully controlled by FIs. This is a logical evolution of business. However, developing new business lines based on platformification or monetization of advanced data analytics (i.e. selling data) provided by FIs to third-party firms is a totally new paradigm and – at least at this time - few are likely to have the capacity for picking up this gauntlet.

Therefore, we would like to share some advice with FI managers as concluding remarks to this document:

- Doing nothing is not an option: while FIs will still exist in the next five or ten years, their role and nature will change; you cannot just simply wait & see;

- Handle and access your data in a better way: develop a data strategy and ensure that some business executives are entrusted with ensuring its implementation;

- Start looking around for partnerships: you can already identify which fintechs are operating in your market and try to partner with them. Likely, the best way to learn is by doing. This will allow you to gain a better understanding of the new challenges to be faced and investments required for such endeavors;

- Promote an innovative culture within your institution: it is easier said than done, but there are strategies to promote innovative culture, such as organization of hackathons, removing silos – creating trans-department working groups, and fostering a corporate culture that is more horizontal.

More than technology itself, your human resources and their freedom to try & fail will position your institution ahead of others in this race to innovation.

1 Big data is usually described as a large volume of data, both structured and unstructured, that comes from a variety of sources, and aims at providing a business with better insights. While big data can be useful to refine some models, most FIs should first aim at collecting and managing “good data”, i.e. data that is meaningful, consistent and up-to-date. This is already a challenge per se, that few FIs, even in mature markets, are capable of addressing in a systematic manner. Big data is on the longer-term horizon but should be kept in mind.

2 PwC. Redrawing the lines: FinTech’s growing influence on Financial Services. What does FinTech mean for financial services organizations: innovation, disruption, opportunity - or all of them? Join the conversation: #FinTech. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/financial-services/fintech-survey/report.html

3 Open banking refers to banks providing access to their systems via open APIs – that is an API documented and usable by anyone (depending on accessibility policies).

4 Ibid, PwC. Redrawing the lines: FinTech’s growing influence on Financial Services

5 Platformification refers to a business model whereby banks sell the use of their systems and infrastructures “as a service” to 3rd-party firms (typically fintechs). For example, if an online lender wants to offer a credit product to the clientele of a bank, this online lender could do this by plugging its own system into that of the bank. The bank would provide services related to infrastructure, providing existing clientele, risk management etc. and earn commission on money lent by this online lender.

Functional separation of sales and credit risk assessment

Overall effectiveness of a financial institution largely depends on its ability to take the right decisions regarding the size and functions of its structural units, the functional duties of its staff, the reporting and communication system as well as on the institution’s ability to recognize the need for making changes and to implement needed changes to organizational structure, processes, procedures and staff requirements in a timely manner.

In this paper, we take a closer look at the advantages of and conditions for separating different functions in crediting small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The purpose is to give financial institutions some food for thought on how they could, if indicated, optimize organizational structure, processes, procedures and staff requirements used to finance SMEs. Obviously, there is not a one-fits-all model but a variety of solutions. Which fits best for a particular institution depends on a number of factors, ranging from shareholder/management preferences to environment, main types of clients, quality of staff, etc. Separation of duties in the lending process for SMEs (and corporate clients) has proven effective in ensuring due diligence in assessing creditworthiness while ensuring a comfortable service environment for clients. The drive for separating duties in serving larger business clients, including SMEs, results from market pressures (which demand more cost-effective and more service-oriented solutions), related investor preferences, international and national practices as well as recommendations made by national supervisory authorities and put forward in international accords.

According to the Basel Committee, the function of credit risk assessment should be separated from the structural business units of a bank. One of the main requirements is complete independence of risk management divisions (both structurally, and financially) from departments that take on risks directly (front offices), register the fact of risk acceptance and monitor exposures (back offices). It is important to rule out any conflict of interest between credit risk management and other divisions of the financial institution. Therefore, a bank (or financial institution in principle) should observe the key organisational principle of separating duties of front office and back offices in the lending process.

|

The mission of the front office is to identify suitable clients, i.e. potentially profitable clients for the financial institution who are able and likely to repay loans on time. And, in the case of a loan application, the front office task is to process the respective application and make an initial assessment of a given client's business. In serving SMEs and corporate clients, front-office staff is often referred to as "client relationship managers" or similar as their main function is to maintain relations with clients and support clients in developing their business, simplifying business operations or overcoming shortcomings by means of offering solutions based on the financial institution’s products and services. In the case of larger clients (larger SMEs and corporate clients) this entails developing individually tailored solutions. Back office staff, often referred to as credit analysts, credit administrators and similar, typically verify the initial analysis and, where required, may conduct a more detailed analysis of the client’s business and application as well as monitor business performance after disbursement. Other back office staff will ensure that the disbursement conditions as determined by loan-decision-making bodies are fulfilled and other contractual obligations fulfilled. |

From the point of view of minimizing credit risk and other risks related to a potentially very close relationship between representatives of the financial institution and a given client, it would be ideal to fully separate duties and have no involvement of the client relationship manager or the ‘sales’ unit in assessing the client and/or loan application and no involvement of the credit analyst in client acquisition and relationship maintenance.

However, this has drawbacks: if credit analysts are too far removed from the actual business generation of the financial institution, they may get so focused on trying to cover for each and every potential risk that lending becomes so cumbersome for the financial institution and the client so that effective demand is too small to make this business a viable and sufficiently profitable venture for the institution. If client relationship managers are only trained in and focused on acquisition and know little or even nothing about credit risk assessment, there is a potential risk that they will spend significant time and effort on acquiring and processing clients and applications that end up as rejections (either by the financial institution or the client) so that, again, effective demand is too small to make this business viable.

Obviously financial institutions need to weigh risk and business opportunities and find the correct balance. This applies to the degree to which duties are separated as well as to which processes and procedures are applied in the lending process. As stated above, there is no one-fits-all solution. Each institution needs an individual solution, based on a detailed analysis of its market, its processes, strategies and goals, its target segments, the professional level of staff, the institution's maturity, future plans and objectives, etc.

Recent experience shows that proper segmentation of clients is crucial in optimizing organizational structures, processes, procedures and staff requirements for working with clients, especially SMEs. More specifically this means understanding which organisational structure, which processes and procedures to apply to the different segments in order to achieve the results the financial institution is aiming for and in order to optimise business performance.

In practice, the two most common approaches to organising duties within SME structural units are: (I) the functions of sales and credit analysis (the front-office and the back-office) are combined; and (II) the functions of sales and credit analysis are separated.

I. COMBINED FUNCTION OF SALES AND CREDIT ANALYSIS

In case of this option, we are talking about a universal loan officer or sales manager whose duties include: (а) active client acquisition and direct sales of (loan and other) products, (b) providing advice to the target client group, (c) analysis of client payment capacity and credit risk assessment, (d) preparation of credit cases for presentation to the respective decision-making body, (e) post-lending support, including (f) working with problem loans.

This approach can work if the numbers that can be generated are sufficiently big and the quality of operations sufficiently high to generate the profit needed to make this approach a viable business option for the financial institution. Therefore, such an approach is typically associated with retail banking and working with micro businesses. In working with SMEs, this approach can be justified if a financial institution has launched SME lending only recently and is planning to go for easy to reach mass market segments, i.e. rather standard clients with standard, simple needs and applications for relatively small loan amounts. In this case, the loan portfolio will be generated as a result of disbursement of loans insignificant in size and with similar credit risk features. Portfolio risk will be diversified and mitigated, i.e. spread over a large number of loans while the risk-and-yield balance of the loan portfolio can be ensured.

In this approach the role of the "universal" loan officer/sales manager is manifold and multidisciplinary.

A key advantage of this approach is that the financial institution creates an environment for the client where all matters can be addressed to one person. For the financial institution this approach has the advantage of allowing for a simple organisation of processes as most is concentrated "in a single pair of hands", i.e. it is easier to set tasks for such an employee and to control performance.

However, this model entails an inherent risk for the organization as it gives rise to possible conflicts of interest and is lacking in safeguards against mistakes and fraud: Loan officers/sales managers may have an inclination to prefer conducting analyses and risk assessment as opposed to selling, or, the opposite may be the case. In the first case, the financial institution may face the problem of many loan rejections and slow portfolio growth, which may even result in portfolio stagnation. In the second case, the financial institution may face inflated disbursements, if staff is focused on pursuing quantitative performance indicators and less concerned with risk assessment. This may lead to a situation where staff - intentionally or unintentionally – may take a negligent approach to analysis and risk assessment. Experience also teaches, that a financial institution choosing this approach may end up with less repeat clients than other institutions - if loan officers are NOT carefully chosen and trained, if NOT fully competent in other products and services of the institution and are NOT given key performance indicators/business targets that take cross-selling, etc. as well as quality of the portfolio and client loyalty into account. Often, at best, we usually will witness a series of consecutive loan applications. Usually, the underlying reason for this does not rest in the client, but in the fact that a "universal", transaction-oriented loan officer/sales manager, who is good at selling loan products rather than other products and services, will focus on selling loans rather than building a relationship with the client, understanding the actual needs of the client and tying the client to the institution by successfully offering other needed services to the client in a timely manner.

The financial institution may miss out on attracting and maintaining suitable clients interested in a broad spectrum of services for whom the institution could plan a long term relationship and potential returns.

In some instances – as in the example provided above – it may be the correct decision by a financial institution to knowingly accept the potential drawbacks described above and go for the universal loan officer/sales manager.

If a financial institution decides to use this approach, it should pay attention to the following three aspects: (1) qualification of loan officers/sales managers, (2) target setting and (3) internal control.

Qualification of staff

For the combined sales-and-analysis function financial institutions need staff equally able to sell and analyse and with a high degree of integrity. Suitable staff needs to be able to quickly sum up situations, analyse situations and draw conclusions/arrive at an assessment. At the same time, suitable staff needs to be sufficiently critical to remain open-minded and able to change assessments in case new information surfaces.

Financial institutions may recruit internally from their base of specialists, if available, or hire experienced loan officers/sales managers from other financial institutions. Usually, for such staff the new position and/or salary will be important. It should also be noted that to grow qualified experts within an institution takes considerable time and resources so that it is important to set stimuli to retain staff. In any case, for both types of experts to be successful, and if financial institutions wish to avoid the drawbacks described above, financial institutions need to adopt suitable hiring and indoctrination procedures, a suitable motivation system and systematic professional training.

Target setting

Target setting should be closely linked to the motivation system. As described above, target setting should be geared to encourage cross-selling and building client loyalty in addition to the other typical items included, such as number and volume of loans disbursed, outstanding portfolio and portfolio quality indicators.

Internal control

It is also important to establish internal controls for all stages of the SME credit cycle, to assign roles effectively and clearly between the different functional units (clear job descriptions, clear assignment of responsibilities and authorities, etc.) and design processes to allow for smooth interaction.

|

Strong internal control, which, in any case, should be an integral part of any financial institution, is of particular significance in case of a combined sales/analysis function to ensure transparency of credit decisions, monitoring results, etc. An effective internal control system requires effective communication channels to ensure that all staff fully understand and observe the policies and procedures relating to their duties and responsibilities. Internal controls should be an inherent part in each business process and ensure that all business activities are in line with established rules and regulations, so as to reduce the likelihood of operating losses and their consequences. With regard to working with SMEs, the focus of the internal control system should be on controlling that the analysis of respective business activities of borrowers are conducted according to the lending technology of the financial institution as well as in accordance with its established policies, procedures and processes, the law and rules and regulations of the regulator. |

Table 1. Internal controls in the lending process

|

Selected stages of the credit cycle |

Front- and back-office functions |

Internal controls |

|

Client acquisition |

|

|

|

Determining suitability/ creditworthiness/ analysis |

|

|

The more complicated processes and functions performed by staff are, the more important it is to pay close attention to internal controls integrated in the process to avoid conflicts of interest, especially if different processes and functions are incompatible from a control perspective.

II. SEPARATON OF SALES AND CREDIT ANALYSIS

Any functional separation should be regarded as a reinforcement of the internal control system and an increase in business process efficiency.

For financial institutions targeting larger clients, - even if not made mandatory by the regulator - it may be worthwhile to give some consideration to separating duties. Larger clients often have complex businesses, are quite demanding regarding the financial institutions and services they use, often require individually tailored solutions and have high expectations regarding professionalism of staff. For institutions targeting such clients, a competent client relationship manager, with whom clients can discuss business issues and possible solutions on equal footing, is the superior option. This approach allows financial institutions to offer a complex of products and build long-term client relationships.

This approach is typically also more appropriate when risks of an individual customer are assessed on an individual basis and loans do not form a pool of uniform loans.

In this approach, the function of the client relationship manager is to acquire as many suitable, i.e. potentially profitable, loyal and long-term clients for the financial institution as possible, identify their needs and develop suitable solutions for, respectively, together with the client. This does not refer specifically to loans but to all products and services a financial institution offers. The client relationship manager acts as a representative of the bank and is the key contact person for the client.

It is of crucial importance that client relationship managers should not only be sales and client oriented, but should also have a sound understanding of analysing businesses, credit analysis and business in principle. Only then can these experts fulfil their tasks effectively and efficiently. As indicated above, sales orientation alone will most likely result in the processing of pointless applications with the outcome of high rejection rates, unhappy clients and ineffective use of institutional resources. Incompetent client relationship managers will also have difficulties in building long term and loyal relationships between client and financial institution. These aspects, regretfully, are often underestimated. Our experience has been that financial institutions often do not give sufficient consideration to the skills, know-how and character traits competent client relationship managers need. Instead, they try to retrain staff from other positions or bring in sales people from other business areas without the necessary experience in assessing businesses, risks, etc.

The functions of a credit analyst include analysis of borrowers’ financial and economic activities, assessment of potential credit and other related risks, preparation and presentation of credit resumes for the risk management and other divisions.

Advantages of the approach:

- building long-term client relationship by providing the client with a continuous counterpart and a product mix that best meets the needs of clients

- an individual approach to each client

- an opportunity for bank specialists to focus on activities they do best

- objective assessment of lending projects and objective credit resumes due to an impartial approach to clients and their business.

In the past, the split was frequently done in such a fashion that client relationship managers just communicated and promoted products and left all actual analytical work to credit analysts. However, experience has shown that such an approach has two major drawbacks: one – as already addressed above – rests in the risk of acquiring and processing unsuitable clients. The other major drawback rests in the approach to the relationship itself. Splitting the sales and analysis function in such a way will lead to a situation where a client has to build up a relationship of trust with different representatives of the bank. This approach makes life unduly complicated and also uncomfortable for clients: during the stages of client acquisition and first interview, the client deals with one specialist, but then all financial data is to be disclosed to another person who is new for the client. This can be stressful for a client and also make retrieval of meaningful and full information more difficult. Therefore, if such an approach is nevertheless deemed most suitable for a given financial institution, it is of high importance for a credit analyst to have excellent communication and social skills in addition to being good with numbers.

As regards this approach, it should also be pointed out that the respective “sales” person and analyst must be able to communicate clearly and fully with each other. In practice, misunderstandings between sales people and analysts are not uncommon and may result in conflict situations, which may adversely affect the quality of customer service.

Model 1 envisages functional separation in all or some regional divisions (branch, directorate, office, etc.) (See Diagram 1).

Model 2 envisages establishment of so-called SME centres providing services for small and medium-sized clients (see Diagram 2). In these centres, a group of analysts gather information, perform credit analyses and assess business activities of potential clients, including making visits to the place of business of clients.

SME centres can be established both on the head office level, and on the regional level. In this model the function of credit analysis is centralized. Centralisation, as a tool, allows maintaining effective processes and internal control. In other words, centralisation is a compromise which ensures continuous customer service on the regional level and optimization of staff costs. However, one should understand that in case of full centralization, the speed of project processing will be lower. Therefore, if a bank focuses on a smaller segment, it may make sense to consider decentralization. Alternatively, if technology permits and access to centralized data bases for verifying clients are easily accessible and reliable it may make sense to fully centralise loan analysis verification and decision-making even for very small business client applications.

In any case, the client – obviously - should be the primary focus of any model adopted by a financial institution to ensure sustainable achievement of business goals. In the long run, clients have the final choice and clients tend to have a long memory when it comes to bad service, unsuitable products, etc.

Thus, if a financial institution plans to optimise its business processes, reorganise structures, and increase operational efficiency, it should take the following factors into consideration: processes, client segmentation, available resources and the qualification level, characteristics, talents and professionalism of the staff, the performance of its information systems, risk appetite, strategy, and the key goals and objectives.

If resources are limited, financial institutions will be ready to get rid of the so-called “sales people” more easily. However, it always makes sense to analyse how these measures would affect the business in the long run.

To sum up, on each stage of its structural development, a financial institution needs to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of its current business processes, analyse their components and quality of the staff involved in each of these components.

“Whenever you see a successful business,

someone once made a courageous decision.”

Peter F. Drucker