Video #1: Gender equality

Video #2: Women market as an opportunity for financial institutions

Video #3: Equal business opportunities for women and men

Video #4: Financing women in business

Video #5: Woman and man - equal opportunities for service

Видео #6: Что значит гендерное равенство для мужчин

Видео #7: Организации на пути к достижению гендерного равенства

But what does financial inclusion mean and why is financial inclusion so important?

The World Bank defines financial inclusion to ‘… mean that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs – transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance – delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.’ 1

Having some form of ‘transaction account’ is a first step toward broader financial inclusion. A transaction account allows for people to keep money, to send and receive money in a safer, faster and more effective way than keeping cash under their pillows, running around with a bag of cash or asking someone else to transport cash for them.

Access to convenient, affordable and safe financial services saves time and effort and allows to use time and resources in more productive and efficient ways. Availability of such financial services also allows to do things that could not be done before, such as taking out an insurance policy for example.

Against this background, financial inclusion has been identified as enabler for a number of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals. Among others, access to financial services can enhance the creation of employment and economic growth, the implementation of green technologies, the reduction of waste or the provision of better education.2

It is estimated that, globally, there still are 1.7 billion unbanked adults.3 And, regarding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion estimates that about half of 400 million SMEs still have unmet credit needs, i.e. 180 to 220 million SMEs. This credit demand totals USD 2.1 to USD 2.6 trillion.4

In short, effectively serving un(der)-banked population and SMEs contributes to enhancing development.

Serving the un(der)banked also presents huge business opportunities.

So, what stands in the way of financial inclusion?

Financial inclusion is hampered by a variety of factors. These include supply- and demand-side issues. The table below lists typical issues:

Point of view of financial service providers |

Point of view of the un(der)-banked, especially SMEs |

|

This client group is not worth the effort (potential profit too low/other, more lucrative, opportunities) |

Available services are too expensive |

|

Addressing this target group is work- and time-intensive |

Available services are not useful/do not meet my needs |

|

This client group is too far away and/or too scattered |

Services are not readily available (too far away, too much effort to access) |

|

This client group cannot meet document requirements |

Services are too difficult to understand |

|

This client group is difficult to understand, has no credit history/there is insufficient information |

I cannot meet the requirements (documentation, collateral) and I often do not understand what the FI wants |

|

This client group cannot meet collateral requirements |

Services are provided by untrustworthy or unknown sources |

While the factors described above hamper financial inclusion in principle, they are especially relevant for SMEs because SMEs, due to their size and comparatively larger financing requirements, fall into a different category than consumers or micro businesses and (very) small enterprises (MSEs). Consumers and MSEs tend to be homogenous target groups. Like small-scale consumers, most MSEs are rather similar in profile and have similar needs. Therefore, it is comparatively easy to define a workable approach, procedures and products for these target groups and reach out to them on a broad basis, now leveraged by new technologies.

In this context, it should be noted that significant headway on financial inclusion in principle has been made in recent years, not least as a result of technical innovations which make out-reach and processing of vast amounts of data more feasible than in the past. At the forefront of this are new communication technologies such as smart phones and digital means of collecting, managing, processing and analysing large quantities of data. Globally, the number of the unbanked has decreased from 2 billion in 2011 to 1.7 billion in 2017. The share of adults with an account has increased from 51% to 69% between 2011 and 2017 (this includes mobile money accounts) and 54% of adults are considered financially resilient (i.e. could mobilise 1/20 of GNI p.c. within one month).5

New technologies as financial inclusion enablers

New technologies are obviously playing an important role in this rapid increase in inclusion. According to Findex, 65% of the 1.7 billion unbanked adults have a mobile phone and 25% have access to the internet and a mobile phone. Digital payments increased from 41% in 2014 to 52% in 2017 and the increase in digital payments is growing faster than the number of account owners.6

52% of adults, i.e. 76% of account owners made/received at least one digital payment in the past 12 months (44% of adults in developing economies) and mobile phone and internet coverage is noteworthy (Gallup World Poll 2017 based on Findex): in high income countries, 93% of adults have a mobile phone, 82% access to the internet and a mobile phone. For comparison, in developing countries, a noteworthy 79% have a mobile phone and 40% access to the internet and a mobile phone.7

New technologies allow to overcome some of the old issues and develop new business models. For example, the use of mobile phones makes distance and costs involved in serving a dispersed and low-volume-per-customer target segment not only feasible but also quite profitable. Use of ‘alternative credit scoring mechanisms‘ and ‘non-traditional information sources’ (e.g. data stored on mobile phones) for evaluating risk, supplemented by new technologies which allow for comparatively cheap data storage and processing of data, help resolve informational asymmetry and collateral issues usually associated with client groups with limited or no reliable data documentation.

As new technologies develop, new business models are developing.

Examples include:

- peer to peer (P2P) financing, i.e. debt financing from individuals for individuals (or small businesses) without the use of an official formal financial institution (FI) as intermediary; usually, an online service matches potential lenders and borrowers

- crowdfunding, i.e. small amounts of capital are collected from a large number of individuals and used to finance a (new) business venture using networks of people/websites to bring lender and borrower (investor and entrepreneur) together

- blockchain technology,e. using a digital ledger where transactions (in some cases relating to or in cryptocurrency) are recorded chronologically and publicly

- Smart contracts: i.e. self-executing contracts, where the terms of the agreement between buyer and seller are directly written into lines of code; the code and the agreements contained therein are available across a decentralised blockchain network; transactions are traceable, transparent and irreversible

- E-commerce platforms: i.e. a platform to allow for/manage commercial transactions conducted online

New technologies and new business models as panacea?

New technologies and new business models are playing an important role in enhancing financial inclusion. But, so far, most fintech lending models proved suitable for rather small amounts only, i.e. for consumer lending and very small businesses (micros) but not for larger amounts and the upper end of the SME segment. Furthermore, in practice not all models proved as sustainably successful as hoped for and resulted in high numbers of arrears/negative effect on the credit history of borrowing individuals or businesses, etc. (e.g. in Africa). A number of platforms have also gone ‘belly up’ (e.g. in China), i.e. ceased to exist due to mismanagement, fraudulent practices or hacking, for example in the case of platforms or blockchains. More importantly, however, is that many offers do not meet the actual needs of individuals and, especially, those of small businesses, i.e. standardised product offers often mean that amounts are either too small or too big to actually fit with what the business needs or that maturities are too short or too long, etc.

So, what about SMEs?

SMEs need comparatively larger amounts than consumers or MSEs. This in itself changes the risk profile and has consequences for the conditions at which financial service providers would be willing to provide financing. Often, SMEs need more individually tailored products than consumers or MSEs, so that a fully standardised approach and product-offer frequently does not match actual needs of SMEs. At the same time, many SMEs still share characteristics with MSEs when it comes to transparency, reliable documentation, documented assets and available collateral. This again has implications for the risk profile and the technology that can be meaningfully applied to assess creditworthiness of applying SMEs. SMEs tend to be diverse, i.e. not as homogenous as target group as the micro segment and low-end of the small segment. Consequently, technologies that can be successfully applied to consumers or MSEs often do not work for SMEs. And this seems to hold true for many of the new technologies and business models as well.

So far, cash flow-based lending, i.e. lending to SMEs based on ‘knowing the customer’, truly understanding actual cash flows, actual assets, profit, history and plans of a business seems the most robust and sustainable model – even if not the cheapest or easiest to implement. And, new technologies can most certainly assist in making this approach more attractive for FIs. New technologies can help in lowering costs related to data retrieval, storage and processing for example. They can also allow to lower costs related to serving clients and reaching out to SME clients on a broader basis.

However, some fundamental issues do not go away just by offering digital services or employing new business models. This includes issues related to lacking financial literacy/financial know-how of individuals and SMEs, unresolved consumer protection issues, other legal and regulatory short-comings, lacking know how of FIs in how to assess SMEs and offer financing tailored to the needs of SMEs as well as lacking availability of long-term finance, ideally in local currency, to be able to offer SMEs tailored (investment) finance. And this is where governments, international financial institutions (IFIs) and other international organisations come in.

The role of governments, IFIs and other organisations

There are conditions and requirements that need to be met to enhance MSME development in principle. And this includes creating the environment in which also new technologies and new business models can operate in a sustainable and effective manner while enhancing actual financial inclusion.

It is up to policy makers and law makers to create the necessary environment. Foremost, requirements and conditions needed for enhancing financial inclusion include:

- Regulation that permits for alternative financing but ensures consumer protection and financial stability

- Functioning credit bureaus/informational infrastructure to support credit risk assessment/store information on credit history/make credit history available

- Government support: public (ideally public-private) risk sharing mechanisms, e.g. guarantee schemes, public-private equity funds; financial literacy campaigns, etc.

IFIs and other organisations can play an important role by supporting governments in creating the needed environment to enhance financial inclusion of individuals and MSMEs by:

- Supporting policy makers and governments in creating the needed regulatory environment and risk sharing mechanisms

- Setting standards for Social Performance Management (SPM)

- Supporting establishment of functioning credit bureaus/informational infrastructure

- Supporting initiatives to enhance financial literacy

In addition, in particular IFIs, can play a crucial role in enhancing access to finance for SMEs by making long-term funding (ideally in local currency) for financing SMEs and technical assistance available to FIs to enhance the knowhow of institutions on how to tailor services to the needs of SMEs.

The Regional Small Business Programme (RSBP) for Central Asia as part of enhancing financial inclusion

The RSBP was created with support of the EBRD and the EU specially to enhance the know-how of FIs on how to serve MSMEs and to encourage the use of digital means (new technologies) in communication and training. More specifically, the RSBP offers (some) class room training and access to online information and training to FIs in Central Asia, with the goal of improving how FIs work with small businesses. By placing the main emphasis on developing the knowledge sharing and exchange platform (KSEP) and encouraging use of the platform, the RSBP is also contributing to the transition of FIs in Central Asia to use of new technologies.

In this way the RSBP contributes to enhancing financial inclusion of SMEs while also contributing to the up-take of new technologies by financial sectors in Central Asia.

[2] The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

[3] https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/

[4] GPFI Report Alternative Data Transforming SME Finance.pdf

[5] GNI p.c. stands for Gross National Income per capita

[6] https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/

[7] Mobile Tech Spurs Financial Inclusion in Developing Nations

The world of training is changing

Financial institutions are adjusting themselves to new realities. The fast progress in IT technologies and digitalization is changing business models and modus operandi of financial service providers. Approaches, which for years were guarantors of success in the financial service business, are now becoming outdated or at least are being put to the test.

Digitalization has consequences for staff needs of financial institutions and their training needs as well. In this article we will raise just a few issues related to how training is affected.

Increasing importance of HR as strategic business driver

Having the right staff in the right job is a key driving force in ensuring sound and sustainable operations of financial institutions. Therefore, continuous staff evaluation, determining staff needs (not just numbers but also qualification levels, etc.), staff development and training should be a priority. As the world in which financial institutions are moving is changing, these aspects are gaining in significance. Whereas digitalization may be making some classic job profiles obsolete as automation of processes takes hold, it is also creating the need for new profiles, new skills and new people: people, who are able to make use of the possibilities of digitalization and people who can do the work that cannot be automated, such as jointly developing tailored product solutions with a corporate business client. All of this has significant consequences for the kind of people needed and for how they should be trained. As a result, HR in principle and staff development and training in particular, are increasing in their importance as strategic business drivers and key to sustainable success of financial institutions.

Ensuring preservation of knowledge and know-how within the institution

Ideally, the process of acquiring new knowledge and retaining already acquired knowledge should never stop. This goes for an individual as well as for a financial institution (or any institution) overall. While this seems obvious, experience shows that the knowledge of experienced staff may be lost as a result of job changes within a given institution or of staff leaving the respective institution for good. In practice, ‘holes’ left by ex-employees are more common than one would have guessed.

In short, in order to build and retain knowledge and know-how, it is necessary to have processes in place for upgrading and retaining know-how. This includes ensuring individuals enhance or at least do not lose existing qualifications as well as ensuring processes for safeguarding that a given institution overall enhances and retains know-how, e.g. through building reserve cadres in a timely manner or developing special courses for refreshing knowledge of staff. But it also means that institutions are thinking about staff in a more strategic manner than before. Staff requirements are shifting to more highly qualified staff. Also, the speed at which actual job requirements are changing is increasing.

All of this means that institutions need to pay more attention to staff selection, staff training and to developing staff over time. This includes paying attention to timing and content of training. It can be rather costly and usually is also not very effective to try and train staff in topics or processes not immediately needed. It is also not as easy as it may seem at first glance (if at all possible) to cross-train staff into new functions. It also means that institutions are having to give more consideration to how to retain staff, i.e. career development planning, evaluation systems, payment systems, promotion systems, etc., as it will not be easy to replace personnel, if lost.

Effective training

Furthermore, the ways in which staff learns are changing. While class room and face-to-face training and coaching remain the preferred option for learning or deepening new skills, simple transfer of information and knowledge can be done more effectively and cost-efficiently by means of online training. - And the younger generations are used to using smart phones and other digital means for procuring information, learning or even practicing new skills in interactive online settings. Last, but not least, institutions need to find ways of training staff without jeopardizing business targets. This means that training sessions should be comparatively short and easy to combine with work. This also entails that combinations of theoretical training and practical training on the job are advisable – not only because of the fact that the trainee can spend more time at work, but also because of the advantages of putting newly acquired knowledge/know-how directly to practical use.

So, to sum up some of the most salient points:

- Just in time: training should be offered to fit with actual job needs to be most effective

- Online training: once set up, online training allows for cost-effective and efficient transfer of knowledge and information. Online training can be effectively used to replace at least part of the classic syllabus of topics especially new employees have to undergo, e.g. topics related to corporate principles, basic learning materials on acquiring, serving and financing clients or similar. As technical possibilities are developing further, online training also allows for effective practicing of newly acquired skills

- Gamification: this is closely related to the above; interactive online games can be used to develop and practice newly acquired skills

- Keep training units short: this increases effectiveness and allows to combine training and work without jeopardizing effectiveness of either the one or the other

- Hybrid training and on-the-job coaching: combining online, possibly class room and on-the-job training allows to put newly acquired knowledge/know-how to direct use – this has proven highly effective in terms of learner success while allowing to control costs and absences from work.

Apart from inviting external trainers, some financial institutions establish their own in-house corporate universities, training centres, or at least delegate training functions to particular specialists. More recently, financial institutions have also started to add online training facilities to supplement other training.

The role and importance of expert-trainers

Usually, trainers working for financial institutions can be grouped as follows:

- Corporate trainers, e. in-house trainers, staff members who administer and implement general training programmes (e.g., "The bank's corporate culture", "Business communication", "Time management", "Effective sales", etc.). The primary function of this type of trainer/HR staff is to organize and implement training. Please, note that this can also include organizing staff participation in certain online training measures and similar.

- Expert-trainers – these are specialists of a particular department of the institution (e.g. SME department) who teach others those things they know and can do well due to their own professional experience and expert knowledge of the subject. For these trainers, training/coaching is usually an additional function, in addition to the duties associated with their day-to-day professional activities. Expert-trainers can also be external experts specifically invited to share specific know-how.

- Experts in developing online training: these are specialists who can convert respective training or informational material into interactive online training.

While all forms of training and types of trainers have their advantages and disadvantages when it comes to cost-effectiveness, effectiveness in actually transferring knowledge and or developing skills it should be noted that corporate universities, etc. and online training – at least for the foreseeable future – cannot meaningfully replace the impact and effectiveness of expert-trainers.

Learning directly from an expert always has been one of the best ways of passing on know-how.

Therefore, we will now turn to some of the methods for identifying, training and developing expert-trainers, i.e. trainers who are knowledgeable in a respective area, have practical experience in this field and are quite capable of passing on this knowledge/know-how and in teaching others on how to do something. Please note, that we differentiated three separate requirements: (theoretical) knowledge, (practical) know-how and ability to train, i.e. to successfully and effectively pass on this knowledge and know-how to others. Finding this combination in staff is not as easy as it may seem. Not everyone who knows how to do something is also good at teaching others. Good teachers may not always have the desired degree of in-depth practical know-how to effectively transfer needed know-how. So the focus needs to be on testing/checking for all three items.

In practice, different financial institutions use different approaches to the development of their in-house expert-trainers.

Suitable candidates

A suitable in-house expert-trainer is an employee who – in addition to sound technical knowledge and practical expertise - enjoys and is talented in passing on knowledge and know-how to others as well as shares the financial institution’s corporate values, understands its philosophy, is aware of the institution’s overall strategy and is ready to follow it. Since, ideally, an expert-trainer does not only conduct training, but also develops training programs, his/her ideas and moral values, motives, and attitudes toward events and people should be in line with those of the institution as trainers actually represent the institution when teaching. When selecting and developing such specialists, special attention should be paid to their interpretation of the institution’s values and corporate culture, their loyalty and attitude towards the institution’s strategy, in addition to screening technical skills, know-how and teaching talent.

Main focus when selecting in-house expert-trainers

Ideally, the term trainer implies that such an expert can implement training but also has knowledge and skills to develop training programs. Financial institutions, however, are often faced with the fact that a corporate trainer, who has general training skills, often lacks specific knowledge and experience to provide training on specialized topics, e.g. analysis of SMEs as compared to micro businesses. At the same time, if we plan to employ for example an SME expert as a trainer, we can be faced with a situation where an excellent professional lacks the personal qualities to be good trainer. In short, financial institutions need to screen for the ability to actually teach others and develop training programs in addition to screening for technical knowledge. This should include teaching in a class room setting as well as – ideally – providing on-the-job training.

Main tasks of an in-house expert-trainer

The range of tasks of an expert-trainer may vary depending on how training is set up at a given institution. Typical tasks of an expert-trainer include:

- Identifying staff training needs, conducting pre-training knowledge testing

- Gathering ideas and planning training courses and programs

- Gathering, studying, and processing data for developing/improving training modules/courses/programs

- Developing training courses/programs, including testing and adaptation, if needed

- Building balanced training programs: developing course material, slides, handouts, tasks, and exercises for knowledge consolidation and skills development (case studies, role-plays, discussions, etc.)

- Conducting workshops, seminars, working groups

- Coaching staff on the job

- Post-training support (Ideally, a trainer would also be able to provide material for subsequent conversion into online training material or would be able to convert material him- or herself)

Expert-trainer selection

Typically, expert-trainers are identified by superiors, who observe staff actually training other staff on the job or as part of staff evaluation by managers and/or by the HR department. It has also proven effective to announce the possibility of becoming a trainer in-house and conduct an internal recruitment process for possible expert-trainers. Like most other professions, a good teacher follows a calling rather than just doing a job, so volunteers, people who like to train are usually more suitable than other candidates – even if they may not yet have acquired necessary didactic techniques, etc.

A candidate for an expert-trainer position must always demonstrate excellent technical expertise on the subject matter in addition to a certain talent for teaching.

After initial identification of candidates based on technical expertise and basic readiness to teach, candidates should be screened more thoroughly by reviewing evaluation results, fulfilment of key performance indicators, possibly interviews or even assessment centers. Assessment criteria should clearly also include aspects related to the candidate’s motivation (interest) in teaching and ability to teach.

Character traits of suitable candidates

Not all technically fit professionals are automatically also good teachers/trainers. Suitable candidates should have the following characteristics:

- Intrinsic motivation to enhance the knowledge/know-how of others/help them approve their skills

- Certain charisma, which allows to spell-bind participants (students)

- Positive attitude towards learners

- Well-developed communication skills, ability to express oneself clearly, concisely and in a structured, easy to understand manner

- Ability to structure information in a logical manner

- Empathy, i.e. the ability to put oneself in the position of the other and a certain broad-mindedness to be able to understand questions or issues learners are grappling with

- Readiness and ability to develop, organize and implement training and training programs

- Ideally, specific qualities or knowledge relevant for the respective area of expertise

Necessary skills

An ideal trainer should be good at methodological work and actual teaching/training/coaching. Apart from profound subject knowledge, an expert-trainer should have:

- Methodological competence — ability to structure content (information/skills/ etc.) and to "pack" them into a concrete training and/ or training program;

- Training competence — ability to effectively transfer or reinforce knowledge, know-how to and build skills in others.

Training of an expert-trainer

In most cases, expert-trainer candidates can be identified who have what it takes to become an expert-trainer in the future. To find somebody who is already a finished trainer is the exception. Regardless of technical expertise in a certain field, developing and organizing training requires certain skills and know-how, i.e. the art of training is a field of expertise as well. In order to be a really good trainer, a trainer should also develop expertise in the field of training.

Most identified candidates will have the talent to develop needed skills and know-how, but will not yet have the knowledge, expertise and skills in training per se. The simplest way to build needed expertise is to put suitable candidates through a train-the-trainer program, where they will learn how to train, how to organize training and how to develop training material and courses. This should be combined with on-the-job training, i.e. being coached by an experienced trainer for some time in training-related tasks. Design and duration of the train-the-trainer program (including coaching) may differ depending on the tasks to be assigned to a given trainer, the institution’s preferences, etc., but certain basic training skills should be covered. Below we provide an example.

After completing initial training as trainer, expert-trainers can then continue to refine and develop their expertise as trainers over time.

Train-the-trainer Example

A bank decided to provide an intensive training course to its trainers. The course will cover basic adult learning tools, group exercises, skills and competencies development assignments, and train-the-trainer methods involving up-to-date concepts.

The Table 1 below lists several modules to be included in the intensive training course:

Table 1: Train-the-trainer modules (a short version)

|

Suggested modules |

|

|

1 |

Fundamental principles of adult learning |

|

2 |

Planning training measures |

|

3 |

Setting learning goals and objectives |

|

4 |

Elaborating seminars/workshops/working groups |

|

5 |

Learning forms and training methods |

|

6 |

Trainer presentation skills development |

|

7 |

Varying the different types of activities during a training session |

|

8 |

Working with an audience (holding the attention of the audience, managing difficult participants, overcoming resistance, question-answer activities) |

|

9 |

Peculiarities of conducting a training |

|

10 |

Pre- and post-training support tools |

One should keep in mind that a training event should always take into account: (a) target orientation; (b) a science-based educational process; (c) a system of teacher-student interaction; (d) evaluation criteria for training results; (e) modern teaching methods, including when and how to use them.

On-the-job training

Following this intensive training course, objectives and plans should be set for the expert-trainer to put newly acquired know-how and skills to use. Initially, this should be done under the supervision of an experienced trainer. This will enhance the further deepening and use of acquired skills in a controlled environment. This serves to prevent misunderstandings of training concepts, etc. or bad practises from taking hold while boosting the confidence of the new trainer in using acquired know-how. In practice, this usually means that a co-trainer (with solid experience) will assist the new trainer in designing training measures and will be present in the classroom when the new trainer implements training. After the respective session, the co-trainer provides detailed feedback. It is the discussion of results, less successful and more successful aspects of the training that will help the new trainer develop and hone his/her training skills. This is mainly based on discussing certain concrete situations, difficult moments, non-standard reactions of students, etc.

The subsequent training process for a trainer should be of a cyclical nature – practice-theory-practice-theory – just like training for any other staff.

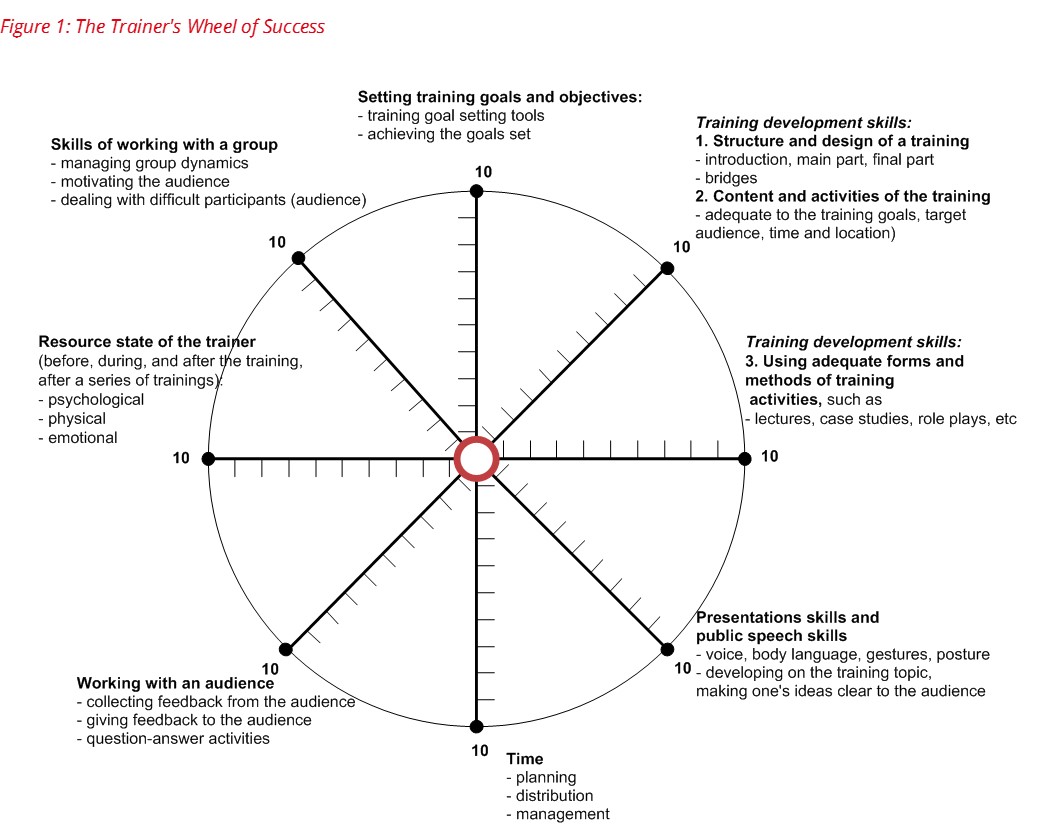

The Trainer's Wheel of Success shows the areas of knowledge, competencies and skills that an expert-trainer should develop and reinforce:

Enhancing and retaining abilities of trainers

One last aspect deserves particular attention. In order to preserve, enhance and further develop the expert-trainer’s technical knowledge, know-how and expertise it is crucial that such trainers continue to work in the field and only teach/train part-time. Otherwise there is a big risk that trainers may lose their technical qualification in the respective field(s). Ideally, information awareness and professional knowledge of expert-trainers should be higher than that of students. At the same time, expert-trainers should also implement enough training to stay in practice and further develop their skills as trainers. This obviously also includes undergoing regular theoretical and practical training as trainer.

In order to optimize the system of expert-trainers, work and career development plans for this staff should take this into account and foresee regular training as trainer, implementation of training-related tasks, working in the field and undergoing technical training in their field to retain and enhance know-how and skills. Financial institutions should also give consideration to building up reserve expert-trainers in a timely manner to ensure smooth operations in case of the loss of a trainer.