The classic challenge of (profitably) serving SMEs for financial institutions

Many financial institutions continue to find it difficult to effectively and profitably serve the SME segment. While there are multiple reasons for this, the SME finance gap is primarily due to three interrelated costs that financial institutions face, which represent challenges inherent in serving SMEs:

Information costs: SMEs are incredibly heterogeneous with varying degrees of formality and are typically more opaque than larger corporations due to a lack of reliable and readily available financial information. This results in high information asymmetries for financial institutions, who cannot necessarily rely on formal financial statements, credit reports, or other documentation, making the cost of assessing credit risk significant. Many financial institutions resultantly rely heavily on collateral, which excludes many SMEs, particularly those with lighter balance sheets. This is a problem in Central Asia, where the value of collateral needed to obtain a loan for a SME varies from 170% of the loan amount in Tajikistan to 227% in Mongolia.[2]

Transaction costs: In addition to the challenge of information asymmetry, the relative transaction costs of serving SMEs may be higher than those involved in serving larger corporate clients or other clientele. This can be due to relatively fixed per-transaction or overhead costs spread over smaller ticket sizes, factors such as distance, (i.e., SMEs potentially being further from branches), a higher rejection rate of SME loans due to higher credit risk, etc.

Opportunity costs: Even if financial institutions identify the profit potential in a fitting SME lending approach, the actual profitability of serving SMEs in absolute terms may pale in comparison to serving larger corporate or retail clients, or, in some contexts, lending to state-affiliated enterprises. In contexts where capital or human resources are constraints, financial institutions may find the opportunity cost of focusing on SMEs too high. Put in simple terms, in almost all markets, SMEs are rarely the “low hanging fruit” for financial institutions.

Given the unique challenges in serving SMEs profitably, most successful SME finance providers have invested in a targeted approach, with SME-related finance as a dedicated segment or profit centre with SME-focused staff, products, and procedures—but this typically requires significant investment and commitment. As a result, any strategy, approach, or technology that can successfully reduce the costs above (without costing too much itself), or mitigate the risks of lending to SMEs, can play a role in facilitating SME finance and enabling financial institutions to more profitably target the SME segment.

The purpose of this paper is to show how a value chain-focused approach, which includes understanding value chains and the position of SMEs in those value chains—often in relation to larger anchor businesses—can enable financial institutions to expand SME finance outreach and profitability.

No business is an island: what are value chains?

But first, what exactly is a value chain?

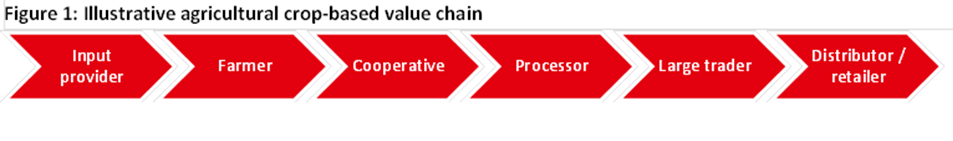

A value chain can be defined as the full range of activities and players that are required to create, produce, and deliver a product or service. In fact, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), all products and services are part of a value chain, whether global or local.[3]

The term value chain is often used interchangeably with the term supply chain, which historically has a stronger focus on operational aspects for businesses: procurement, production, and logistics. The term value chain, on the other hand, was coined by renowned business author Michael Porter in 1985 and focuses more on the series of activities that adds value to a product or service at each step, ultimately transforming it to a final good or service. While traditionally value chain analysis focused on the value added by a single business (or business unit) to a good, the value chain concept is used broadly today to consider entire sectors (e.g., coffee or shoe production).

The term value chain is often, though by no means exclusively, used in an agricultural context, highlighting the process, players, and value added to bring agricultural goods from farms to consumers. The term is equally useful in other contexts or sectors, however, particularly where goods are processed or produced, from the complex with a multiplicity of actors and activity levels (e.g., airplanes or mobile phones) to the more basic (e.g., food or small commodities).

Regardless of the terminology used, all financial institutions naturally recognise that the majority of their business clients—including SMEs—are part of business chains with an upstream (suppliers) and a downstream (buyers/customers), and that the success of their business clients (and the financial institution’s credit risk) is heavily influenced by this chain. The value chain perspective is helpful for better understanding relationships between value chain actors, as well as the sequence of all relevant activities along the chain.

While value chains may be domestic or global—that is, stretching across multiple countries—most SMEs in Central Asia are focused on the domestic market, and thus the discussion in this paper focuses on domestic value chains.

Value chain finance for financial institutions

A key feature of several value chains is the presence of a major or anchor business. Such a business is typically a larger corporation, potentially affiliated with a multinational, that has a relatively dispersed “upstream”—i.e., multiple SME suppliers—or a dispersed downstream—i.e., multiple SME retailers or vendor businesses. Depending on the position of the anchor business (e.g., up or downstream), anchor-driven value chains are often referred to as buyer-driven or producer-driven chains.

While much analysis typically focuses on the good(s) being produced by a value chain, a helpful view of value chains focuses on value chains as a series of linkages involving regular and predictable exchanges between players (particularly around anchors) of the following:

- Goods and services – flowing downstream, ultimately to the consumer

- Finance and funds – flowing upstream to producers and suppliers

- Information – flowing both ways, though not always recorded or consolidated

Very few value chains are characterised by the immediate settlement of transactions, and thus credit is a natural and critical component of almost all value chains. Value chain players, particularly anchor businesses, often extend forms of credit, including even longer-term financing, which may sometimes be delivered or repaid in kind.

Table 1 shows information on the percentage of firms using banks and supplier/customer credit to finance working capital in four Central Asian countries—all below the global average.

Table 1: Key Central Asian indicators

|

|

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Tajikistan |

Uzbekistan |

All countries |

|

% firms with a bank loan/line of credit |

17.2% |

25.8% |

18.0% |

22.2% |

33.1% |

|

% firms using banks to finance working capital |

13.2% |

18.8% |

12.8% |

23.7% |

30.0% |

|

% firms using supplier/customer credit to finance working capital |

20.7% |

6.4% |

12.4% |

2.9% |

29.5% |

Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys[4]

The presence of flows of goods, funds, and information between actors creates a value chain finance (VCF) opportunity for financial institutions.

Good-practice MSME credit analysis and underwriting approaches at financial institutions focus on the individual SME business in question, understanding the ability and willingness of the business to repay. In this way, this approach tends to view each SME as an independent entity, and an exhaustive analysis of the SME’s upstream or downstream usually only occurs if the SME is particularly reliant on a specific supplier/buyer or contract, i.e., there is potential concentration risk.

VCF instead takes a holistic approach, seeking to understand the overall structure and nature of the value chain, identifying suboptimal elements of the chain in terms of finance provision, particularly liquidity gaps, and then identifying opportunities to provide profitable financial products and services to businesses within that value chain.

Effective VCF approaches typically focus on relatively integrated and stable value chains, and often centre around an anchor business or businesses—often existing clients of the financial institution—and seek to leverage the position of the anchor to mitigate risk and provide financial services to suppliers or buyers.

Anchors often already engage in the provision of finance to value chain actors themselves as a means of ensuring stable supply or timely delivery, developing loyalty, or promoting sales. “Outsourcing” this financing to a specialised financial institution can be attractive to anchor businesses for a variety of reasons, including freeing up working capital and improving liquidity, reducing administrative and transaction costs, de-risking the balance sheet, simplifying collection, receiving commission income, etc.

Additionally, although value chains are often graphically displayed in a linear fashion, it can be helpful to think of a wider web or ecosystem of indirect chain actors, including equipment suppliers, logistics providers, information services, employees, regulatory bodies etc. As such, by focusing on the ecosystem as whole, financial institutions can leverage existing clientele and their extended networks to more effectively reach new clients and cross-sell products (e.g., payment transactions, payroll services, letters of credit etc.).

The value of collaboration: partnerships with value chain players

Typically in VCF some form of strategic alliance is established between a financial institution and one or more value chain actors—typically the anchor—to reduce transaction costs and lower risks that otherwise impede access to traditional financial services.

Typically, through a partnership, the anchor may offer the following to financial institutions:

- Information: The anchor can provide critical information on upstream or downstream SME (and other) actors in the value chain, including the provision of referrals or introductions, borrower screening, transactional data, sector-specific data, contract or document verification (e.g., purchase orders or invoices), credit need information, etc. Such information may assist financial institutions in identifying or assessing potential clients, allowing them to “outsource” elements of credit assessment.

- Transaction facilitation: The anchor can more directly support the facilitation of financial transactions, whether through directly supporting loan disbursements, co-signing, establishing reverse factoring schemes etc.

- Guarantees: The anchor may provide guarantees or engage in other risk-sharing mechanisms (e.g., co-signing, buyback schemes) to mitigate credit risk and indirectly facilitate transactions with SMEs for financial institutions.

From the anchor’s perspective, formal or informal partnership with a financial institution may facilitate either procurement or sales/distribution.[5] For the financial institution, such collaboration allows for the reduction of information asymmetries and transaction costs, as well as the expansion of service. The specific nature and depth of partnership with the anchor(s) must be defined on a case-by-case basis by the financial institution based on its analysis of the value chain and negotiations with the anchor.

Potential risks in value chain finance

Engaging in value chain finance presents potential risks and challenges for financial institutions as well that must also be considered, perhaps the most obvious of which is the concentration risk resulting from having a significant amount of exposure related to a single value chain or anchor company.

As SMEs supported through VCF approaches are likely part of the same value chain(s), covariate risk may be a serious issue, with external or other influences negatively affecting multiple businesses simultaneously.

Systemic risk is also a challenge, with the possibility of idiosyncratic risk at one value chain player (particularly the anchor) rippling up or down the value chain, creating a literal “chain reaction”. As a result, linked businesses may suffer, again creating potential covariate risk, particularly in strongly linked value chains.

As a result, a careful analysis of the value chain is critical, and a deep understanding of the linkages between businesses in the value chain is required.

Financial institutions should also carefully consider and establish concentration or exposure limits to value chains and sectors to mitigate such risks, as well as ensuring strong monitoring and risk control systems over time.

Anchoring the approach: developing value chain finance at a financial institution

So what can a financial institution do to effectively establish a VCF approach?

Successfully utilising VCF approaches requires a clear understanding of the nature and risks in a value chain as a whole, and the identification and assessment of a fitting anchor business with whom to collaborate. This is a move away from assessing the credit risk of each individual SME borrower, typically resulting in higher upfront costs for financial institutions, but, if done correctly, with the potential to scale those costs over many clients and achieve economies of scale with reduced individual transaction costs.

The following are potential steps for financial institutions to get started:

1) Identify potential anchors and their value chains: Assuming that a financial institution has already engaged in corporate and/or SME lending in a market, it is often beneficial to start by identifying the value chains in which existing financial institution clients—particularly potential anchors—are participating. As a first step, larger or more significant corporate clients may be identified, considering the depth, longevity, and nature of the business relationship between the financial institution and the potential anchor.

From this initial scan, a “shortlist” of potential value chains and anchors may be established. A thorough due diligence of a potential anchor business should be conducted (or previous analyses updated), with the goal of not only understanding the anchor itself but the value chain in which it participates. As VCF approaches typically involve a formal or informal partnership with the anchor company, at this stage aspects of reputational risk in partnering with an anchor should already be considered, as well as the anchor’s potential willingness or interest in collaboration.

A benefit from using existing clients/sectors as a starting point is that the financial institution or financial institution staff may have existing knowledge and/or expertise in the relevant sector.

2) Map the target value chain: The presence of a strong potential anchor business does not necessarily indicate an ideal target value chain. As much as possible, financial institutions should focus on value chains demonstrating strong integration and higher levels of liquidity. The more linked a value chain is, the more reliable are the flows of goods, services, liquidity, and information between the players and, all things equal, the lower the default risk of a particular business within the value chain.

Financial institutions should thus “map” value chains, identifying the anchor(s) and players, the links between them (and the strengths of those links), and potential weaknesses. During this step, the financial institution should take care to confirm that the potential anchor business identified in the first step actually is indeed the prominent company in the value chain, demonstrating strong negotiating power with SME suppliers and buyers.

Quantitative and qualitative criteria regarding the value chain should also be considered, including: the recent development of and structural changes in the sector/industry, production volatility, price volatility, reliance on domestic/foreign markets, volatility of financial flows, policy issues/risks, formality of relationships, negotiating power, etc.

Box 1: The dairy value chain in the Kyrgyz Republic[6]

|

Value chains naturally vary, with each Central Asian country have its own dominant domestic sectors and prevalent value chains. Taking the Kyrgyz Republic as an example, a key value chain is the dairy value chain, which provides milk both for domestic consumption and export.

The majority of fresh milk in the Kyrgyz Republic (70%) is traded by smallholder family farms in the form of fresh milk. Although annual milk production is 1.5 million tons, only 8-10% of milk is processed by milk factories. In the dairy value chain, milk factories (15 of which are permitted to supply milk to the EEU) are potential anchor businesses, typically buying milk from upstream milk collectors (agents) and selling through domestic retail networks or trading partners/exporters. Kazakhstan and Russia are major export markets for processed milk and dairy products (butter, cheese, yogurt, ice cream). Both milk farmers and collectors seek better access to finance and improved interest rates, with milk farmers often covering a significant portion of their operating costs through finance if possible. Value chain finance approaches may allow partnership opportunities with milk factories to improve financing to milk farmers and milk collectors in the Kyrgyz Republic. |

Based on this, the financial institution should develop a clear understanding of how each player in the value chain adds value, as well as a detailed understanding as to the current financial needs and practices of the players.

3) Identify business opportunities: Based on the mapping and understanding of the value chain, and potentially in coordination with the anchor business, the financial institution can identify potential entry points and business opportunities in the value chain.

Such opportunities may often be based around shorter-term liquidity needs or gaps, but may also involve longer-term asset financing opportunities. Additionally, financial institutions may attempt to identify opportunities to cross-sell or offer a suite of products to value chain players.

Common VCF instruments include:

- Short- and medium-term credit (e.g., lines of credit)

- Equipment leasing

- Medium- and longer-term credit (e.g., vendor financing for equipment purchases)

- Current accounts and transactional services (e.g., payroll, POS)

- Receivables financing (e.g., factoring, bill discounting, forfaiting, reverse factoring)

- Collateralised financing (e.g., repo financing, warehouse receipt financing, inventory financing)

- Letters of credit and letters of guarantee

- Insurance

- Derivatives (futures, forwards, options, swaps)

During this step, formal cooperation with the anchor company may also be defined and negotiated. What service (if any) will the anchor provide (e.g., data, guarantees, referrals), and what will the anchor receive in exchange for this (e.g., commissions, discounts, branding, etc.)?

4) Set targets and concentration limits: The financial institution should set risk parameters (portfolio limits), as well as define a risk monitoring approach to ensure that these limits are adhered to at the portfolio level. At the same time, targets should be set to spur financial institution staff to achieve economies of scale and take advantage of the value chain opportunity.

5) Implement and adapt over time: Ideally, while the financial institution may wish to pilot the approach within a single or small number of value chains, a larger number of value chains (and anchor businesses) are considered in order to diversify and ensure limited exposure to a single sector or value chain. Attempts should also be made to explore additional ways to reach the ecosystem surrounding the value chain as possible.

Value chain finance in the digital age[7]

While VCF approaches and concepts are hardly new, the emergence of new digital tools and technologies, including the recent explosion of data availability and data processing capabilities, has created new opportunities for innovative financial institutions to explore VCF schemes. The potential value of such digital VCF approaches has only increased with the acceleration of digitisation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic globally.

Supply chain digitisation promoting transparency and data availability

The increasing usage of digital tools and digitised interactions within value chains has made data regarding physical and financial transactions more available and transparent. Activities previously conducted physically (e.g., by paper, in cash, in person) are increasingly recorded or monitored digitally at each stage: contract signing, ordering, tracking goods, delivery, sales, payments, etc. As a result, data regarding the frequency of purchases or sales, interactions with suppliers and customers, and inventory turnover are now more available, allowing for increasingly tailored and automated credit risk assessments and decisions by financial institutions. This data availability may alleviate the need for an anchor to provide detailed information, or supplement the information provided by an anchor.

Transformational impact of platforms

The increased use of a variety of digital platforms has created opportunities for VCF approaches with value chains that might have been seen as relatively fragmented or small-scale in the past. As transactions are increasingly facilitated by digital platforms that further track and consolidate information, financial institutions can particularly consider platforms as partners in aggregating value chain players and collecting the information necessary for providing value chain finance. Partnering with digital platforms can allow financial institutions to receive detailed, and in some cases real-time, transaction data and other relevant information. Examples of platforms include e-commerce platforms such as Alibaba or Amazon, national e-invoicing hubs, fintech-provided platforms, etc.

Opportunities remain to be ahead of the curve in many markets

Digital financing based on digital transactions throughout value chains is already increasingly prevalent in many countries around the globe, but many opportunities remain, particularly in emerging markets—such as those in Central Asia—and in value chains that are presently more fragmented (e.g., multiple smaller-scale producers and buyers, fewer repeated transactions). The increasing availability of data can reduce information and transaction costs for financial institutions, allowing such institutions to provide finance more efficiently, further incentivising shifts towards digital approaches and the digital integration of value chain players.

The new opportunities brought about by digital disruption for financial institutions are coupled with new challenges. Potential collaborators (e.g., fintechs, platforms) may also be competitors in the provision of VCF as barriers to entry (e.g., informational costs, transaction costs) have been reduced by the presence of technology.

[1] MSME Finance Gap: Assessment of the Shortfalls and Opportunities in Financing Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Emerging Markets. International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2017. (https://www.smefinanceforum.org/sites/default/files/Data%20Sites%20downloads/SME%20Report.pdf)

[2] As quoted in OECD 2017 “Enhancing Competitiveness in Central Asia” (p 47). (https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264288133-5-en.pdf?expires=1607683633&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=6128AC11281F3DAC0F5F5747CE96872F)

[3] A Rough Guide to Value Chain Development: How to create employment and improve working conditions in targeted sectors (ILO), 2015, 2.

[4] www.enterprisesurveys.org. Accessed on 16.12.2020.

[5] A classic “win-win-win” value chain finance example is when a financial institution lends to a (SME) producer based on a contract with its (anchor) buyer, replacing the need for the anchor to provide credit. This frees up working capital at the anchor, facilitates credit for the producer (perhaps on better terms), and allows the financial institution to lend to a new SME client with reduced transaction costs.

[6] The content of this box was adapted from: ADBI Working Paper Series, Leveraging SME Finance Through Value Chains in the CAREC Landlocked Economies: The Case of the Kyrgyz Republic, Kanat Tilekeyev, (ADBI, No. 972), 2019.

[7] This discussion has been heavily influenced by: Technology and Digitization in Supply Chain Finance (IFC), 2020.

How to register at the platform

How to signup for online courses and get certificate

While cybersecurity and risks related to cybercrime have been growing priorities for financial institutions (FIs) for over two decades, the COVID-19 crisis has abruptly “changed the game”, forcing FIs to change practices abruptly and adapt to new ways of operating and communicating.

Most FIs have been on a digital journey for some years now with the goal of improving efficiency and leveraging technology to provide better financial services to clients. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment efforts, the digital agendas of many institutions have been unexpectedly accelerated or reengineered in a time of emergency. Movement away from physical branches and towards more mobile services and digital communication have become a necessity, and these changes in strategy have and will continue to trigger exposure to risks and the implementation of new practices at different levels of FIs.

This new reality is taking hold and impacting all individuals who have to adhere to home confinement and social distancing guidelines amidst the pandemic. Employees have had to shift to remote working arrangements without sufficient preparation or training in understanding and knowing the limitations of and changes required for this new way of working. As new digital channels for clients are utilised during the emergency to access FI services, new threats have emerged and new practices need to be established. For the institutions themselves, the initiation of changes on the structural level are required to ensure that new threats posed by new working models do not come at the cost of security.

|

Cyber-criminals’ arsenal |

|

Cross-site-scripting attacks, are exploits in which the attacker attaches code onto a legitimate website that will execute when the victim loads the website. For financial institutions, this can be a significant risk if an institution ends up being responsible (or at least perceived as responsible) for infecting their own clients. Distributed Denial of Service (DDOS) is a malicious attempt to interrupt the normal traffic of a targeted server, service or network by overwhelming it or its surrounding infrastructure with a flood of internet traffic. Phishing is sending emails through a fake website supposedly from a trusted institution to gather personal identifiable information such as passwords, bank account details, social security numbers, or to infect the computer of the target. Some phishing approaches are specifically targeted to FI employees, with the idea of getting them to open an attachment or to click on links which then redirect them to a fake website where they are encouraged to share personal identifiable information. Once a cyber-criminal gains access to an employee’s email account, (s)he will be able to:

Ransomware attacks are caused by a type of malicious software or malware designed to deny access to a computer system or data until a ransom is paid. Such an attack on a financial institution can cause monetary damage. |

Cyber threats are not new. However, amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, the increased number of people working from home and/or using digital channels for banking has created an ideal environment for cybercrime to thrive and for cybercriminals to use the weapons at their disposal in a more aggressive way.

Working from home and employee protection

The pandemic has triggered a sudden and rapid increase in employees working from home, as well as an urgent need to provide digital banking services to clients of financial institutions. While cyber threats are not new, amid the global pandemic, cybersecurity-related risks have significantly increased. In particular, the following are key cybersecurity-related challenges:

- Exposure to cybercrime for employees working from home

- Deployment of secured digital channels for banking service provision

- FI ability to detect and respond to cyber threats

While working in an office environment, employees usually adhere to company policies, which include certain controls regarding cybersecurity, such as rules on device set-up, firewall protection, internal network access controls, regular anti-virus updates etc. However, by working from home, employees are working away from the secured office environment, and, therefore, often operate from less secured Wi-Fi networks and from devices that are not set up according to the company’s policy controls. This makes employees more vulnerable to cyber-attacks. Employees working from home are most likely faced with phishing and social engineering attacks. Normally when an employee requires remote access, appropriate training and secured devices are provided. However, with the unexpected and increased demand for remote access to enable employees to work from home, it is possible that adequate protection has not been applied to remote access.

Remote Access to Software

Financial institutions should consider all remote access as medium to high risk and adhere to the following approaches for secure remote access:

- Multi-factor authentication for all remote user access, as passwords alone can be easily compromised.

|

The new standard: multi-factor authentication |

|

Multi-factor authentication is one of the most effective controls you can implement to prevent unauthorized access to computers, applications and online services. Using multiple layers of authentication makes it much harder to access your systems. Criminals might manage to steal one type of proof of identity (for example, your PIN) but it is very difficult to steal the correct combination of several proofs for any given account. Multi-factor authentication can use a combination of:

Something the user inherently possesses (such as a fingerprint or retina pattern) |

Within the past 5 years multi factor authentication has gone from a high level security measure to the gold standard in regards of security for online actors.

- Strong password policies should be in place. A password policy that requires at least a minimum of 6 digits, with a random combination of characters, numbers and lower and upper case letters is stronger.

- Corporate virtual private networks (VPNs) should be employed instead of utilising remote desktop protocols (RDP) over the internet. Limited and secure access by VPNs can significantly reduce the attack surface if any.

- The private computers of employees not provided by the FI should be connected adhering to the FI’s policy regarding anti-virus software and anti-spy solutions, as well as subject to the application of certain security settings in web browsers.

|

What makes an antivirus solution “good” |

|

Antivirus suites take the hard work off your hands by offering automatic security against a host of threats

- Secure home Wi-Fi connections should use a stringent security protocol (e.g., WPA2) and change the default user names and passwords on home networking equipment, such as Wi-Fi routers.

Good Practices for virtual meetings

Remote working has increased reliance on video and audio-conferencing applications, but these tools are increasingly targeted by cybercriminals. Financial institutions should configure these tools to limit unauthorised access, and to make sure that employees are given guidance on how to use them securely. Financial institutions should establish corporate policies for virtual meeting security and educate staff on following them, as they leverage the technology for meetings with colleagues and clients.

- All meetings must require an access code or password

- Do not share meeting IDs on social media unless meeting is intended to be open to the public

- Limit the reuse of access codes to prevent uninvited eavesdroppers, as codes might have been shared with former employees or past clients

- For sensitive topics, use one-time PINs or meeting IDs, and consider multi-factor authentication for joining the meeting

- Use a waiting room for participants who log in before a meeting starts, and only allow the host to start a meeting

- Use a tune when attendees log in and ask new attendees to identify themselves

- If available, use a dashboard to monitor attendees, and identify all generic attendees

- Do not record the meeting unless it is necessary

- If it is a web meeting (with video), remind participants not to share sensitive information

Measures for data loss prevention

Employees may be using unauthorized personal accounts and applications, such as email accounts, and other unauthorized applications. FIs should remind employees regarding the following:

- Avoid sending email correspondence from corporate mail accounts to private mail accounts

- Use only company-approved USB devices on computers used for work

- Designate how and where sensitive information should be stored, using either external media, the institution’s centralised file server or a cloud-based service

- Make regular daily backup copies of all valuable information residing on your device. Data backups are crucial to minimise the impact if that data is lost, corrupted, infected, or stolen

- Ask employees to keep work devices for professional use only and lock their devices when they step away from them. An innocent activity on a work computer could lead to a breach

Reaching clients through digital channels

Digital channels and products have become critical channels for FIs to interact with, engage with, and offer banking services to their clients as the entire sector steers through the uncertainty arising from the pandemic. There has been a spike in the deployment of digital products and channels by financial institutions mainly on the following technologies and platforms below:

- Mobile apps

- Chatbots

- Internet banking

These channels are open and available to the public, allowing anyone to download them. Once registered for a service, a user can immediately use the service for interactions or transactions. These digital banking channels provide convenience and control to the client, but, at the same time, FIs need to guard against having vulnerabilities in such public-facing systems that could be used in orchestrating a cyber-attack.

The urgency of deploying a mobile app should not be a trade-off for fitting security. Each of the above digital channels comes with their own characteristics as described below and requires specific security considerations.

Mobile apps

Mobile banking apps are a preferred digital channel of choice for many due to the proliferation of mobile devices. Mobile apps allow customers to carry out most banking activities without requiring a visit to a branch, including checking account balances, transferring funds, paying bills, viewing statements, managing cards directly and reaching out to customer support. Over the years and pre-COVID-19, the number of users who transact on mobile apps has been growing at a phenomenal rate, surpassing the number who are transacting at branches in many countries. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, mobile apps have experienced a further surge in usage.

With an increase in popularity, comes increased cyber risk. There are three areas within the mobile technology chain where attackers may exploit vulnerabilities to launch a malicious attack, namely: the device, network and the data centre. Device-based attacks target the mobile device itself, exploiting a vulnerability on the device to orchestrate a cyber-attack. For example, an attack can be initiated through phishing or a drive by download, where a visit to a website triggers a download of a malicious code without the knowledge of the user. Network-based attacks, on the other hand, exploit the vulnerabilities on the network through which the mobile device is connected. For example, applications on the mobile device with no encryption for data exchange, when used on an unsecured Wi-Fi network, run the risk of data being intercepted by an attacker eavesdropping on the Wi-Fi network. Data centre attacks target web servers and databases, with the attacker exploiting vulnerabilities in operating systems or applications modules running on the web server.

Chatbots

Chatbots have been around for a while but are still new to many users. For FIs, chatbots are a highly beneficial technology for interacting daily with customers, with the capability of integrating with AI-powered technology for customer interactions. How this technology is used in the financial sector should be in line with the regulations of the sector, protecting customer information from third parties.

Financial institutions are now deploying chatbots on social media channels such as WhatsApp, Telegram, Viber and Facebook Messenger, with a range of banking services such as account balance checks, funds transfers, viewing mini statements, customer onboarding and the paying of bills.

Internet Banking

Internet banking has been around and evolving for decades now. Internet banking offers customers an easy way to monitor their finances, allowing them to view payments, check account balances, update personal information and access other banking services online via a secured website. This easy access makes internet banking a common target for hackers and other cyber criminals. Understanding the security issues related to internet banking can help both FIs and clients to stay safe from intruders. The key in addressing vulnerabilities in internet banking is adhering to the guidelines for digital channels addressed in the table below.

|

Securing digital channels |

|

Adapting the organisation to the new challenges

In an era of increased usage of digital channels and technological transformation, as well as intensified usage of clouds and broader networking capabilities, the threat landscape continues to increase, and threat actors will try to simultaneously attack operational systems and backup capabilities in highly sophisticated ways, potentially leading to enterprise-wide destructive cyber-attacks.

FIs can improve their defense mechanisms and attack readiness by maintaining good cyber hygiene, setting up and maintaining a current incident response strategy, a response architecture and by implementing cyber recovery solutions to mitigate the impact of cyber-attacks.

Good cyber hygiene is a reference to the practices and steps that financial institutions and their employees take to maintain system health and improve online security. Regular implementation of a few key practices can dramatically improve the security of any system:

- Provide employees with regular communication and awareness messages, including basic security knowledge:

- Beware of phishing, especially COVID-19 scams and fraudulent COVID-19 websites

- Know working from home “DOs & DON’Ts”

- Ensure home Wi-Fi is secure

- Always use VPN on public Wi-Fi

- Create a shared channel called #phishing-attacks or an email address to which suspicious emails are forwarded

- Identify critical financial workers in order to ensure undisrupted availability of services for customers

- Review contingency plans to address the COVID-19 pandemic

- Update your company’s Acceptable Use Policy to address working from home and the use of home computer assets

- Identify functions that can only be undertaken in a secured environment at the office (i.e. not remotely)

- Review and adapt disaster recovery plans to the current context

- Provide protective technology on endpoints (hardening, anti-virus, endpoint detection and response, etc.)

- Enforce software updates

- Utilise a password manager or run password audits

- Provide VPN access and disable split tunneling

- Enable multi-factor authentication everywhere, especially on email accounts

Practical steps for a secure environment

The main solution for the reduction of threats is to make sure that there is a high degree of awareness among employees and, where possible, clients. Several tools can be used for this purpose:

Awareness seminars, where the subject is discussed among employees or clients, including sharing the experience of those who have been subject to an attack. These seminars should be aimed at refreshing employees' knowledge of minimum requirements regarding information security:

Email security, to ensure staff know how to keep their emails secure

- Avoid opening emails, downloading attachments, or clicking on suspicious links sent from unknown or untrusted sources

- Verify unexpected attachments or links from people you know by contacting them through another method of communication like a phone call or text message

- Do not provide personal information to unknown sources like passwords, birthdates, and especially, social security numbers

- Be especially cognizant of emails with poor design, grammar, or spelling as this can be a sign of a phishing attempt

Password protection

- Enforce the use of strong passwords on all corporate user accounts

- Avoid easy-to-guess words like names of pets, children, and spouses as well as common dates like birthdays

Web safety

- Make sure that any websites that require the insertion of account credentials like usernames and passwords, along with those used to conduct financial transactions, are encrypted with a valid digital certificate to ensure your data is secure. Secure websites like these will typically have a green padlock located in the URL field and will begin with “https.”

- While FIs employees are working remotely, ensure that they are not using public computers and/or logging into public Wi-Fi connections to log into accounts and access sensitive information

- Sign out of accounts and shut down computers and mobile devices when not in use

Device maintenance

- Keep all hardware and software updated with the latest, patched version

- Run company-approved antivirus or anti-malware applications on all devices and keep them updated with the latest version

- Create multiple, redundant backups on daily basis of all critical and sensitive data and keep them stored off the network in the event of a ransomware infection or other destructive malware incident. This will allow you to recover lost files, if needed

Phishing simulations, which consist of sending phishing emails which redirect recipients to a page explaining the issue and what could have been the consequences if this would have been a genuine attack

Technology training, to be used when new technologies are implemented to ensure that procedures are well understood and that the limitations and dangers of using new technologies are clear for users

Information access and distribution. Centralising all communication materials that FI is going to use in crisis management into one place is a great way to make sure that the right information reaches the right employees at the right time. Employee communication platforms (intranets), as well as regular daily emails, can be used for the timely communication of all necessary information.

COVID-19, a catalyst for digital transformation

The COVID-19 crisis has brought about significant change in perceptions towards and the application of remote working and alternative channels in a short timeframe. The ripples of these changes will impact financial institutions for years to come and will influence the shape of a different world: a seamless world in which all channels are used by all types of clients for different purposes, a world in which financial services offered are the same whether you use your mobile or go to a branch. While the COVID-19 crisis did not create these technologies or approaches, the crisis has been a catalyst and an accelerant, creating both the opportunity and necessity for financial institutions to establish today the digital practices and procedures that will be required tomorrow.